After three years of consultations, the Productivity Commissioner, Peter Achterstraat, and NSW Treasurer, Dominic Perrottet, have published the White Paper report, outlining pathways to improve living standards for the state’s citizens and reduce debt without additional taxation.

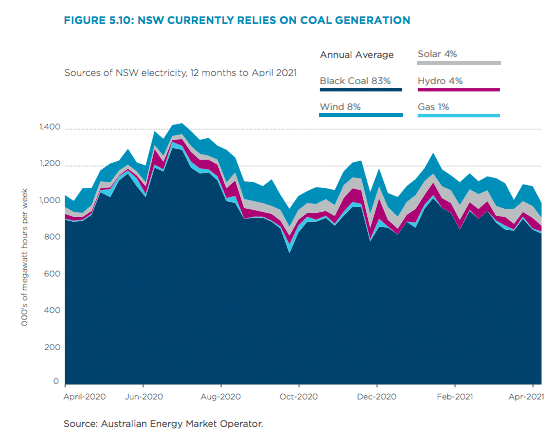

Energy and water policy were both points of focus in the 371-page report, which lays out the history of Australia’s National Electricity Market (NEM) and where its framework has failed to serve Australia’s most populace state, New South Wales (NSW).

History of Australia’s National Electricity Market

Australia’s National Electricity Market (NEM) is a wholesale market covering New South Wales, Queensland, Victoria, South Australia, Tasmania, and the Australian Capital Territory. When it was established by the states in 1998, they separated electricity conglomerates into individual entities dealing with generation, transmission, distribution, and retailing.

As the NEM was created, so too were the Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC), to make rules for the NEM; the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO), to operate the NEM; and the Australian Energy Regulator (AER), to enforce the NEM’s rules, including those determining how much revenue transmission and distribution network companies can earn.

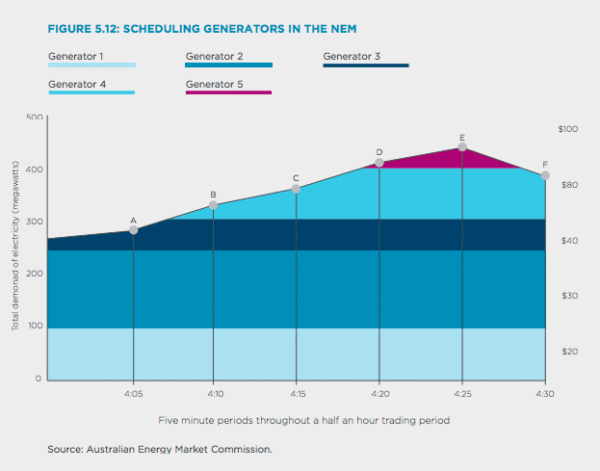

In reality, the NEM consists of two markets: a spot market where generators competitively bid to supply power at any point in time, and a contract market in which retailers and generators make deals to supply power over longer periods, around one to three years on average.

NSW and the NEM

“In New South Wales, generation and retail were privatised and the transmission network company TransGrid became the subject of a 99-year lease. The state is a minority shareholder in metropolitan distribution businesses, with only regional distribution assets remaining completely in government hands,” the report, titled ‘Rebooting the economy,’ reads.

“The NEM initially delivered stable retail prices [in NSW]… but unanticipated challenges prompted ad hoc and costly interventions and, from 2007-08, prices started to rise significantly. Other interventions imposed additional costs that pushed retail prices higher still.

“Recently, prices have moderated. But consumers continue to feel the impact of the earlier actions,” the report reads. As of 2021, retail electricity prices in Sydney are 228% higher than when the NEM was established, compared to an increase in Consumer Price Index (CPI) of 74% over the same period.

The White Paper strategically highlights this price hike in the state before turning to the NEM’s generation reliability standards, which were introduced following the 2016 South Australian blackout. This standard, the paper argues, has pushed up prices even further. “Reliability of electricity is important but this cannot come at a disproportionate cost.”

“Owners of generation, transmission, and distribution assets need to invest to comply with New South Wales and national reliability standards. There are signs that these standards demand more reliability than energy consumers are willing to pay for.”

The report cites research which suggests customers worry more about the price they pay for electricity than about its reliability. “In 2018, about 70 per cent of customers were happy with the reliability of their electricity, but only about 40 per cent were happy with overall value for money.”

Stemming from this, the White Paper recommends NSW policy be developed and implemented within the NEM’s governance structure to ensure there is less duplications of state and national reliability measures. “The NSW Electricity Strategy commits the Government to review the National Electricity Law and Rules to identify national regulatory burdens that can be removed, streamlined, or clarified,” it concludes.

Importantly, Australia’s Energy Security Board, which consists of AEMC and AER chairs, AEMO’s chief executive, together with an independent chair and deputy chair, is in the process of finalising its redesign on Australia’s NEM. Presumably while significant changes in the markets structure unfold on a national level, areas of shortcomings in the states could be addressed more readily.

2050 carbon emissions reduction targets

The White Paper also criticises the Commonwealth or federal government’s lack of interest in imposing a clear 2050 reductions target. “Instead, Australia is now attempting to reach net zero using a series of uncoordinated and inefficient state and territory policies.”

“The most efficient policy to meet the net zero aim would be to put a price on carbon… but the lack of Commonwealth support means that for a national mechanism to be achieved, the states and territories would need to coordinate among themselves.”

The paper recommends, therefore, investigating “new and innovative approaches to improve electricity pricing and achieve the NSW Government’s 2050 target of net zero emissions.”

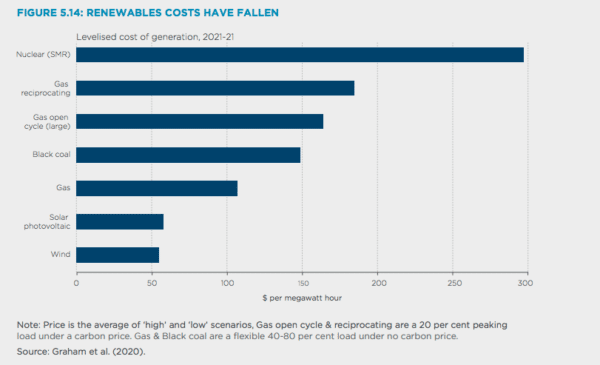

Among its other energy recommendation, the White Paper, which follows on from the state’s Green Paper published in August 2020, calls for a lift on the ban of nuclear electricity generation for small modular reactors, improved land use regulation and manage demand for gas and a streamlining of energy subsidies.

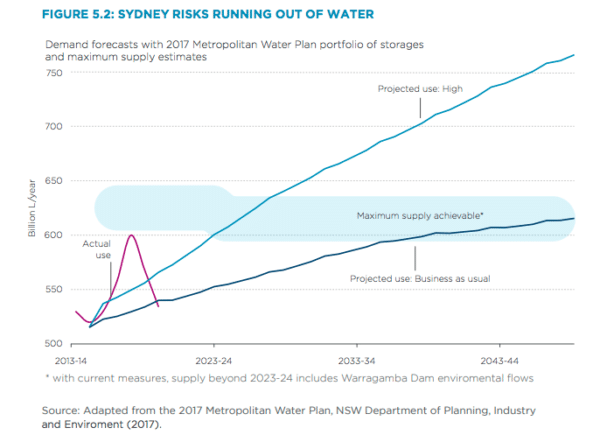

Precious water

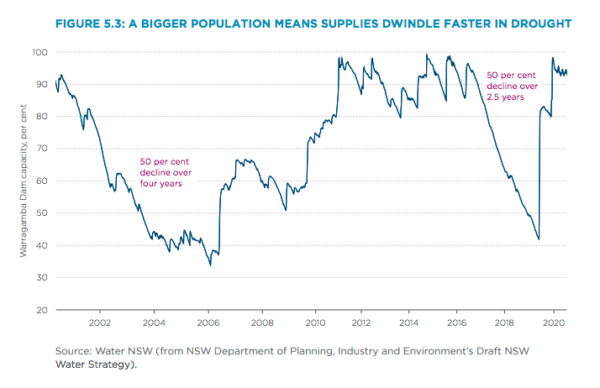

The White Paper focuses heavily on water, which is a particularly sensitive issue in NSW which has suffered a series of major droughts in the past decades, with a number of regional towns literally running out of water in 2019.

The Commission recommends the state government, which has been severely criticised over its water management, set a long-term vision and plan for the sector as well as engaging the public on the benefits of purified recycled water for drinking and explore investments that demonstrate and built trust in the recycling process. It also recommends water be managed in ways which “maximises benefits for the community.”

Issues around water and social license have come acutely into focus recently in Australia as the country’s hydrogen plans ramp up. Water is an essential component of hydrogen production. While the amount of water needed for hydrogen production is far less than mine sites use, given the industry’s novelty and the highly politicised nature of renewable energy in the country, many have forecast that issues around water use and social license should be anticipated by the burgeoning green hydrogen industry.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.