On Friday, the Australian Local Power Agency Bill 2021, which was introduced to Parliament in February by Independent Member for Indi, Dr Helen Haines, was the subject of a public hearing held by the House of Representatives Standing Committee on the Environment and Energy. The Committee heard evidence from many of the individuals and organisations – such as Farmers for Climate Action, the Clean Energy Council, City of Greater Bendigo and Repower Shoalhaven — who contributed more than 1,000 submissions received on the bill over two weeks mid-year.

“The Committee’s inquiry provides an opportunity to hear and consider all viewpoints, in order to advise the House on the merits of the Bills,” said Committee Chair Ted O’Brien MP in advance of the event.

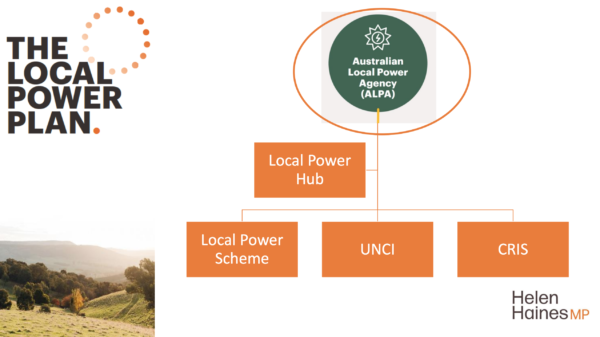

The proposal for an Australian Local Power Agency (ALPA) grew out of Haines’ Local Power Plan, which was launched in September last year after consultation with communities and energy experts on how to “unlock the benefits of community energy”.

Haines had identified more than 100 community energy groups in Australia, many of which were struggling to implement projects, because of a lack of finance, underwriting, limited human resources and access to expertise.

She said when tabling the ALPA Bill in February, “regional Australia should be home to the world’s best renewable energy industry, and we should harness that power of that industry to deliver a generation of prosperity for everyday regional Australians”.

Knowledge sharing and financial support for community renewables developers

Under the Plan’s Local Power Scheme, one of three pillars of the proposed ALPA, is that 50 Local Power Hubs would be established across Australia — from Esperance in WA, to Gippsland in Victoria, to Cape York in Queensland — to provide local organisations seeking to get renewable energy projects up and running, both technical and project support, and strategic development capital from a new $310 million Local Power Fund.

“At the moment we’re all doing great stuff, but working in silos,” Walter Moore from Repower Shoalhaven in NSW, told the Committee on Friday.

Local Power Hubs will alleviate the constantly repeated learning curve, with “peer-to-peer capacity building”, “shared resources” and providing “technical support across communities”, says the Local Power Plan.

Three “schemes” are key to the Plan, which is seeking an overall $483 million of Federal funding over 10 years: the Local Power Scheme is complemented by the Underwriting New Community Investment (UNCI) Scheme, which will provide financial certainty to proposed mid-scale energy projects (generation and/or storage) that are at least 51% community owned, which Haines says will “unlock billions of dollars of private investment to support communities to build their local energy independence and resilience”.

And the Community Renewables Investment (CRIS) Scheme will introduce a requirement that local communities be able to purchase 20% project equity in large scale renewable developments planned for their area.

This third component of ALPA is likely to become the most contested.

Image: Local Power Plan

Burnout in the volunteer sector

Both written and verbal submissions to the Committee were largely in favour of the ALPA Bill, with organisations such as Renewable Albury Wodonga (RAW) Energy, presenting evidence of the burnout experienced by under-resourced volunteer organisations passionate about enabling the energy transition at a community level, and sharing the benefits.

RAW Energy has been particularly successful in its community education, sourcing funding for installation of solar on low-income housing, gathering data in support of further initiatives, modelling a mid-sized solar farm for the region and assisting with the establishment of a community energy retailer, Indigo Power — among other activities.

Its representative Narelle Martin wrote in RAW’s submission that the organisation has learned that volunteers can become very thinly stretched, and “volunteering needs to be enjoyable for people to continue their engagement and contribution”. Also that, “Volunteers may not have the skills required for technical and financially complex projects.”

The organisation’s hopes for ALPA are high, saying it would reduce the pressure and expectation of volunteers to help develop critical infrastructure; it would provide access to new financial streams that can “improve the financial resilience of regions”; and it would accelerate the ability of rural and regional communities to share in the social and financial benefits of local renewable energy generation.

Where RAW sees the potential for the Community Renewable Investment Scheme to provide fairer access for project-hosting communities to the financial benefits of large-scale renewable-energy projects, the National Farmers Federation (NFF) expressed “reservations … with respect to profit-sharing arrangements as set out in clause 30 of the Bill”.

David Jochinke, Vice President of the NFF board, said his membership believes that ALPA would help address the problem experienced by farmers that they are typically not included in early consultation by organisations such as the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO), when planning new energy infrastructure.

The NFF written submission to the Committee cited decisions on AEMO’s Integrated System Plan, and the Western Victoria Transmission Network Project had been made in advance of community and local council consultation, such that, “While greater investment in electricity generation has created significant opportunities for regional Australia, the benefits do not necessarily flow nor contribute to the development and growth of regional communities.”

Its submission went on to say that ALPA, “would address these crucial gaps by empowering regional communities and regional stakeholders to be involved in the decision-making process, rather than central authorities”.

Is local community buy-in to multi-million-dollar projects untenable?

Then although the NFF said it agreed with the principle of local benefit sharing by large project developers, “the concept of 20 per cent of the profits going to people living within 30 kilometres (km) appears prescriptive and may even deter investment”, it said, adding that it “would welcome the exploration of new models” to achieve the same benefit-sharing outcomes.

The Clean Energy Council’s written submission by Anna Freeman, the organisation’s Policy Director for Energy and Hydrogen, said the industry also objects to 20% mandated profit sharing, though not to benefit sharing per se.

Freeman noted on behalf of the CEC’s membership that profit sharing is not mandated “on any other form of major infrastructure development in Australia”, and is therefore inequitable, and singles out a sector which is on average performing better than any other form of energy infrastructure in Australia in terms of sharing benefits with the community”.

No Minister!

The CEC also expressed “grave concerns” about the Bill’s proposal to require Federal ministerial approval of projects involving construction, modification or expansion of large renewable energy generation facilities in Australia, when such projects are already go through a process of approval for development under state planning laws, unless there are foreseen implications of a project under the Environment and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 — as has been the case with the mega Asian Renewable Energy Hub in the Pilbara region of Western Australia.

Freeman submitted that affording the Federal Minister powers of approval over such projects “would represent a significant overreach in Commonwealth powers and would create another layer of complexity and uncertainty for investment in an already challenging regulatory environment”.

On behalf of Repower Shoalhaven, Moore addressed another salient point in Haines’ reasoning for a community-focused agency, which is that established and successful agencies — such as the Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA) and the Clean Energy Finance Council (CEFC) that have supported innovation in renewables, and the development of large-scale clean energy projects, tend to support corporations and major investors.

Repower Shoalhaven, for example, has developed rooftop solar for local organisations and businesses such as a joint project covering Nowra Bowling Club (45kW), Eagle Park Dairy (30kW) and Ogden’s Timber & Hardware (20kW); and its most recent project, the 3 MWac Shoalhaven Solar Farm to be co-developed with innovative energy utility Flow Power, opened for investment by members this month.

“We never quite ticked the boxes,” to receive funding from existing agencies like ARENA, Moore told the Committee.

Keep renewables under the expertise of our renewable energy agencies?

On this point, however, and despite supporting the aims of ALPA, Freeman also questioned the need for a new and separate agency to administer the necessary financial and technical support. She wrote that the CEC suggests these functions “could be effectively implemented by an existing agency if that agency’s mandate and funding were to be increased accordingly.”

The Committee hearing, which began at 9.30am on Friday, wound up at 4.30pm with Haines tweeting, “Thanks so much to everyone who gave evidence today and to the committee members for their thoughtful questions.”

The ALPA bill has certainly highlighted, as Claire Ferres Miles, CEO of Sustainable Victoria said on Friday, that communities want to act on climate change, but currently encounter many barriers to participation — there is an important role for govt-funded staff to support volunteers in community power hubs.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

Very interesting, I’ll check it out. I note that local communities “being able to purchase 20% project equity in large scale renewable developments planned for their area” and ” 20 per cent of the profits going to people living within 30 km” are two quite different things.