From pv magazine 04/2022

It was a Saturday morning when Sydney-based billionaire Mike Cannon-Brookes, partnering with Canadian investment giant Brookfield Asset Management, put in a shock bid to buy Australia’s biggest power company AGL. The massive “gentailer,” which has both generation and retail operations, is also the country’s biggest carbon emitter.

The plan, according to Cannon-Brookes and Brookfield, was to take control of AGL, close its coal fleet, and replace it with billions of dollars worth of renewables by the end of the decade. It would be the world’s largest single decarbonisation project, they said. “It sounds like posturing bullsh*t, but it’s actually not at all. It’s 100% correct,” Tim Buckley, director of Climate Energy Finance, told pv magazine. By his calculations, the play would cumulatively avoid 289 million tonnes of CO2 emissions.

AGL generates 20% of all the electrons traded in Australia’s National Electricity Market (NEM) and supplies almost one-third of its households. Overwhelmingly, this supply comes from three geriatric coal fired power stations: Victoria’s Loy Yang A, which AGL currently forecasts will retire in 2045, and the neighbouring Liddell and Bayswater plants in New South Wales.

By the following day, AGL’s board had rejected the bid, which valued the company at around $5 billion. AGL’s CEO described the figure as “ridiculously low.” Nonetheless, the news commanded headlines for weeks, described as a “new dawn” for a country where coal closures are a kind of quicksand, gobbling the careers of prime ministers, chief executives and activists alike. Excitement was spurred by Cannon-Brookes and Brookfield’s promise to continue pursuing the company with its new capitalist trojan horse model.

For Cannon-Brookes – the co-founder of software company Atlassian who famously bet Elon Musk $50 million via Twitter to deliver a 100MW battery to South Australia in 100 days (he did) – Australia’s coal sinkhole needed a sidestep. The 42-year-old billionaire found an ideal partner in Brookfield, which is currently creating the world’s largest fund for renewable investments, the Brookfield Global Transition Fund, which is headed up by Mark Carney, one of the most influential climate change power brokers in the world.

“The beauty of this strategy from Brookfield and Mike Cannon-Brookes is that there are investors out there who are willing to take on that political risk,” said Leonard Quong, the head of Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF) Australia said. Something listed Australian companies, like the 185-year-old AGL, “don’t really have an appetite for,” he added.

Instead of prying fossil fuels from the cold dead hands of incumbents, Cannon-Brookes and Brookfield would simply purchase them, along with a mammoth customer base and nationwide sites adorned with remarkable transmission connections. For Josh Martin, the director of sustainability solutions for Engie Impact Australia, the play was “capitalism at its finest.”

On March 6, two weeks later, Cannon-Brookes and Brookfield came back with a fresh bid, sweetening their offer by 10%. AGL’s board, once again, took just a day to turn it down. Cannon-Brookes responded on Twitter with a GIF of Doctor Who crying in the rain, saying he would be putting down his pen “with great sadness.”

Buckley, like the director of the Victoria Energy Policy Centre, Bruce Mountain, thinks this ends the battle, but not the war. “That is round one,” Buckley said. Mountain echoed his sentiments, saying he suspects “they are still interested in one way or another.”

Both Brookfield and Cannon-Brookes’ Grok Ventures confirmed to pv magazine they will continue to seek decarbonisation opportunities in Australia. The players, it seems, are still in the game. “They’ve certainly pointed out what can be done,” said Martin.

Taylor snubbed

A week before the surprise takeover play hogged headlines, it was announced that Australia’s largest coal plant, Eraring, would bring forward its retirement to 2025. The new date is seven years earlier than originally scheduled, and just three-and-a-half years away – the bare minimum under current rules. “That in its own right was a huge milestone for 2022,” Buckley said. The early closure solidified a major change in strategy for Origin, Eraring’s owner and Australia’s second-biggest power player after AGL.

Eraring, the company said, was simply no longer suited to the “rapidly changing conditions” in the NEM. The news shocked many, including Australia’s federal energy minister. For some time now, Australia’s state and federal levels of government have been moving in different directions on climate and energy. The pandemic turned that drift to a tidal wave.

“Nationally, we haven’t gotten anywhere close to bipartisan agreement on emissions reduction or energy policy, and we’re no closer to that now than we’ve ever been before. Whereas at a jurisdictional level, we have got there. All the states are there,” said Mountain.

The bipartisan consensus at the state level was most notably seen in the populous states of New South Wales and Victoria, both of which have legislated globally ambitious renewable energy plans. As Origin itself pointed out in its recent company strategy, the plans put the states on track to respectively meet between 50% and 80% of their power demand with renewables by 2030. South Australia will reach its goal of 100% renewables before 2030 and Tasmania is eyeing 200%, looking to profit by exporting green electrons.

Meanwhile, Australia’s federal government has allowed the country’s COP26 Pavilion to be sponsored by oil and gas giant Santos, something Buckley described as “criminal.”

This growing gulf widened further on the announcement of Eraring’s accelerated closure. Origin CEO Frank Calabria, who was appointed in 2016 to steer the power company into the low carbon future, had in fact approached the government long before, reaching out to New South Wales Environment and Energy Minister Matt Kean.

The company and Kean’s office worked together on the closure plan for more than half a year, during which time no information was passed along to the federal government, nor the relevant minister, Angus Taylor – and this despite both Kean and Taylor belonging to the same conservative Liberal party. The secrecy was reportedly at Calabria’s behest and proved wise.

As soon as Origin made the closure plan public, Taylor took to talkback radio to describe the plan as “very disappointing,” and fostering fear of generation shortfalls and the necessity of increased generation from natural gas. As his colleague, Prime Minister Scott Morrison, put it soon after: “Our government is very committed to ensure we sweat those assets for their life.”

This continued rhetoric from the federal government, supporting gas and undermining renewables and energy storage, has seen it increasingly excluded by the more ambitious states. After more than a decade in power, the federal government has now found itself in an unusually weak position, particularly on climate change and energy policy, just weeks out from an election.

Moreover, as Buckley notes, in a world where “billionaires rule the roost,” the Morrison government now has two of Australia’s richest three pitted against it: Mike Cannon-Brookes and mining billionaire Andrew “Twiggy” Forrest.

Closing coal

“The reality is the economics of coal-fired power stations are being put under increasing, unsustainable pressure by cleaner and lower cost generation, including solar, wind and batteries,” Forrest told the Queensland Media Club in February, quoting Origin’s CEO from his Eraring closure statement. “When the coal sector itself says that, you know the end has well and truly come,” Forrest added.

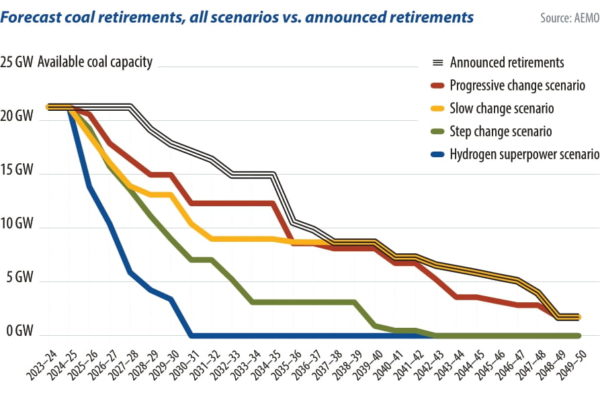

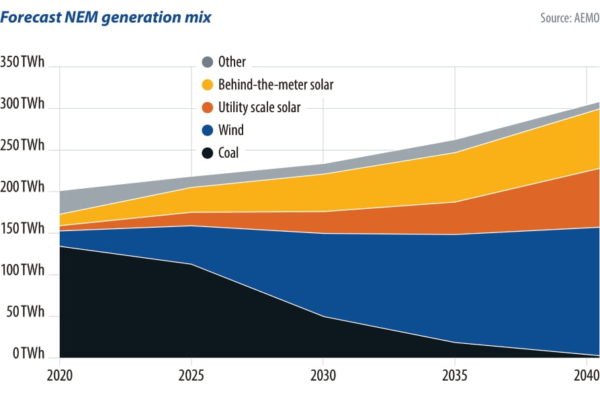

According to Australia’s Electricity Market Operator (AEMO), Australian coal is now retiring two to three times faster than anticipated. In 2020, AEMO delivered its first “Integrated System Plan,” which laid out possible routes for Australia’s transition. Just one year later, in December 2021, AEMO revised what is considered Australia’s most likely route, moving to a “Step Change” scenario. In doing so, it drastically brought forward its coal closure forecasts from phasing out by 2051, to the expectation that “all brown coal generation and over two-thirds of black coal generation could withdraw by 2032.”

This amounts to a serious misalignment between when coal plants are publicly said to close, and when they’re actually dropping off. While chaotic, Ben Cerini, a principal consultant at Cornwall Insight Australia, believes few remain naive. AEMO’s revised system plan “suggests no one believes any of the generators around when they say they are going to retire their coal fired generation fleets,” he told pv magazine.

Batteries at coal plants

Where solid ground does exist is in the consensus that coal plants are ideal sites for Australia’s preferred storage technology: big batteries. A number of retired and retiring coal plants today either have big batteries in construction or in planning.

At Engie’s mothballed Hazelwood coal plant, which caused power prices to soar when – back in the naivety of 2017 – it gave just five months’ notice before closing, work has begun on a 150MW/150MWh battery. Just down the way, a 350MW, four-hour battery is being planned to replace the Yallourn coal-fired power station when it retires in 2028. And at Eraring, Origin is moving forward with a 700MW battery to be built in two stages, the first of which will have a capacity of 460MW and two-hour duration. Origin told pv magazine it will work with the state government “to support installation of as much of this battery as possible, before any closure of the coal-fired power station.”

These are just a few examples of a sweeping trend. Cornwall Insight estimates Australia’s storage pipeline in 2021 at 26GW, up from 7GW in 2020. The construction of this pipeline, says Cerini, is rapidly being realised. “In the last six to 12 months, people have started building robust business cases around the acquisition or development of those sites. That’s the change that we’ve seen firsthand.”

AGL is planning 850MW of grid-scale batteries, with 13 projects underway to transform thermal sites “into integrated, low-carbon industrial energy hubs.”

Not fast enough

Despite this activity, AGL is still not moving fast enough. Buckley, Mountain and investors agree on this, as evidenced by the company’s share price tumbling 73% over the past five years. Buckley estimated that AGL has “destroyed” $5 billion to $10 billion in shareholder value. Big funds have sold out, with no institutional investors today holding more than a 4% stake.

From this precarious position, AGL said last year it plans to “demerge,” splitting into two separate entities. The first, AGL, would become a retail, storage and supply business. The second, to be named Accel Energy, would hold the generation assets, mostly coal. The AGL board is adamant the demerger will be a “catalyst for the potential realisation of shareholder value,” though Buckley likened the plan to cutting the Titanic in half in the hopes one side would float. “That’s a deliberate attempt to solve the rehabilitation liability problem,” Buckley said, referring to growing understanding that fossil fuel companies’ bonds in Australia aren’t enough to cover the rehabilitation of their sites.

AGL’s shareholders vote on the demerger in coming months. “Cannon-Brookes and Brookfield will likely bide their time, and see how things develop,” Buckley said. “If we get a change of government and/or the shareholder approval of the split doesn’t reach 75%, the pressure will build.”

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

7 comments

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.