A project seeking to demonstrate the potential of ocean energy in Australia was unveiled today at the Australian Ocean Energy Group’s Market Summit in Hobart.

The project is being proposed near Albany, on Western Australia’s southernmost tip, and at this stage involves a concept vision which will progress, later this year, through a feasibility analysis and business case study with the Xodus Group, where the concept will be refined.*

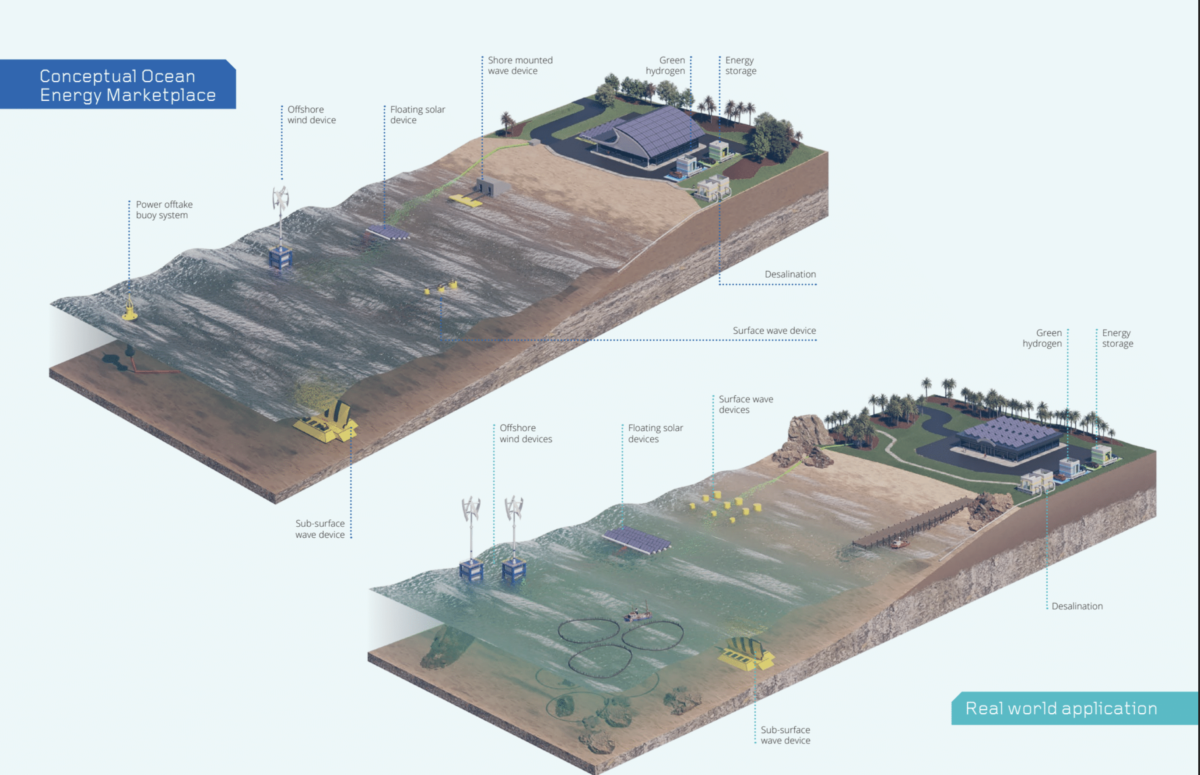

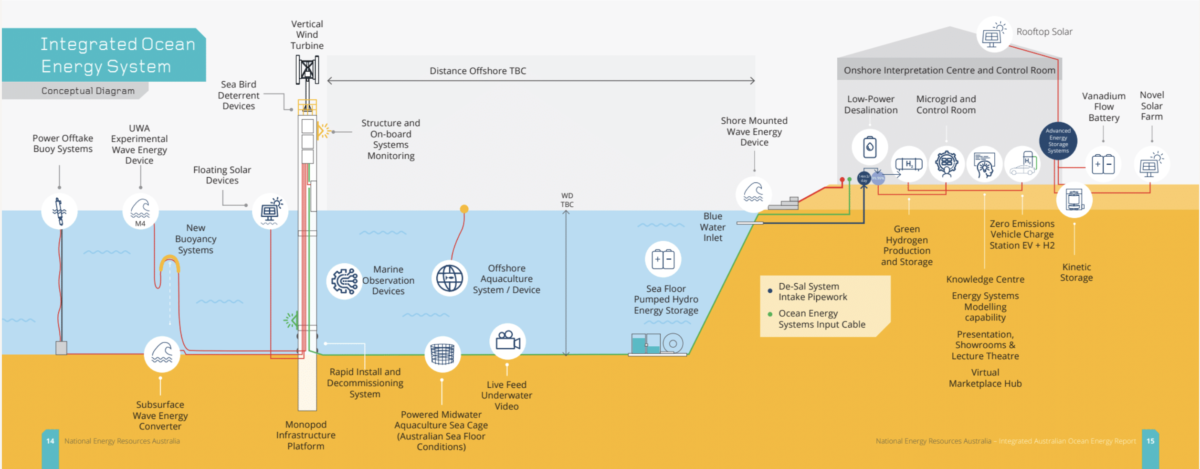

If found to be feasible, The project will unfold in two stages, the second of which will see the development of “a physical, visitable marketplace” which will showcase an integrated ocean energy microgrid.

“Using an integrated microgrid approach, a working, pilot-scale ocean energy system will be created as a world-first offshore energy marketplace,” the announcement says, though precisely what this means isn’t quite clear.

The project is being led by the Australian Ocean Energy Group cluster, which was established with support from NERA (National Energy Resources Australia), and seeks to illuminate the benefits of integrating ocean energy with other renewables, including offshore wind.

There is already a project looking to create an ocean energy centre, named Marine Energy Research Australia (MERA), in Albany. It is being led by the University of Western Australia (UWA) and backed by funding from the state government. That project partners with local company Carnegie Clean Energy and will involve the deployment of an experimental wave energy converter call the M4.

Alex Ogg, NERA’s Ocean Energy Program Manager, told pv magazine Australia this will be the “first device in water as part of the physical marketplace in Albany,” adding that his team is working with MERA on the parallel projects.

Ogg said the NERA Marketplace project, however, is technology agnostic and separate from the MERA centre.

Ocean energy

The promise of ocean energy is neither new nor mastered, with attempts to harness its power documenting all the way back to 1799. Since then, thousands of patents have been filed and as many inventors risen and fallen.

In Australia, there are a handful of companies grappling with the technology, including Carnegie Clean Energy. Carnegie was involved in UWA’s Marine Energy Research Australia project before the company went into voluntary administration in 2019. It has since bounced back and is again working on the centre, looking to further ocean energy in Australia.

Image: Carnegie Wave

Carnegie’s journey illustrates some of the challenges ocean energy expert Richard Manasseh, Swinburne Professor of Fluid Dynamics, outlined to pv magazine Australia earlier this year. He noted the scale and cost were the most problematic aspects of ocean energy projects, inhibited the technology’s takeoff more than actual technological issues.

“The machines don’t work at all unless they are gigantic,” Manasseh said. “So there’s a mismatch between the amount of capital companies tends to have and the size of what they have to build.” Wave energy machines can cost anywhere from a few hundred thousand to a few million to build, depending on the design’s sophistication and efficiency.

Stephanie Thornton, who heads up the Australian Ocean Energy Group cluster, echoed these sentiments saying the four main barriers to the adoption of ocean energy are awareness, accessibility, affordability and commercial project delivery.

While these issues have set back the technology in the past, Ogg says the ocean has “almost limitless potential to produce clean energy more consistently and predictably than any other source.”

“Energy from our oceans has been too often overlooked. What also sets ocean energy apart is its ability to be integrated with other renewables — from discrete blue economy applications today to multi-use offshore energy parks in our future — adding huge value, consistency and complementary energy to the renewable supply,” Ogg added.

Given that the project is expecting to develop its second stage, the “physical marketplace,” in Albany in 2023 – 2024, it would suggest the project is primarily based off modelling rather than submerging actual ocean energy machines in West Australian seas.

Nonetheless, the announcement outlines the stage two microgrid “will include a combination of wind and wave energy converters, solar (onshore and/or offshore), storage and application technologies including green hydrogen production, desalination capability and EV charging.”

Ogg confirmed the project is intended to have both physical and modelling components, but it remains unclear whether the physical component is simply the information centre in Albany or if it extends further ocean energy and other renewable devices. “There will be a physical plant based in Albany at the Historic Whaling Station, who will host the interpretation centre and amplify the public message around wave energy through their visitation and educational outreach programs,” Ogg said.

“This facility will incorporate wave, wind and floating solar technology in the form of a demonstration microgrid, with localised distribution.”

“There will also be a digital portal, accessible globally, with the intent of both to bring energy transition market customers into contact with ocean energy technology developers and project delivery teams to catalyse commercial projects.”

Another large ocean energy modelling project was announced earlier this year, involving researchers from Melbourne’s Swinburne University, Adelaide University, and the University of New South Wales working in collaboration with Victoria’s Moyne Shire Council and Western Australia’s Mid West Ports Authority. It is looking into whether ocean energy devices could be used to protect Australia’s vulnerable coastlines.

*This article was amended on May 18 to include additional information and comments.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

1 comment

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.