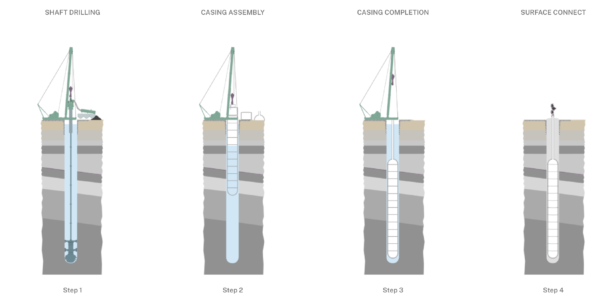

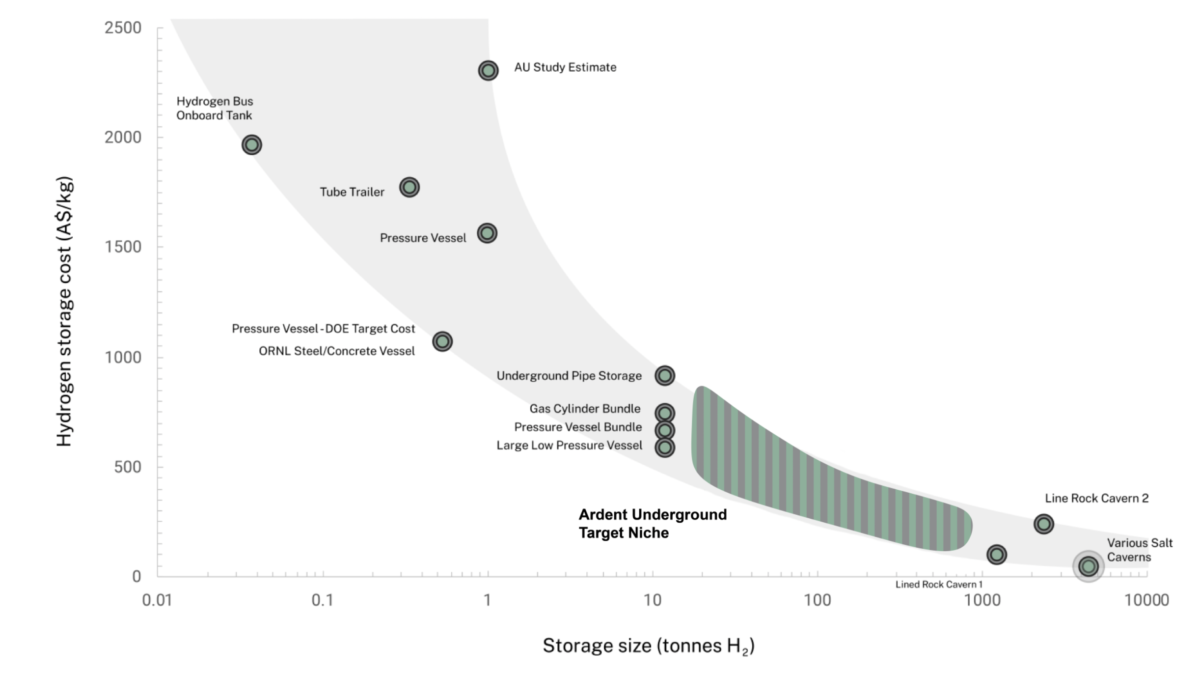

In 2019, Australian engineering firm Abergeldie Complex Infrastructure launched its ‘Ardent Underground’ vertical hydrogen storage solution. Building on the company’s previous boring technology, the design is a purpose-built deep shaft to house compressed hydrogen – not too dissimilar from salt cavern notion.

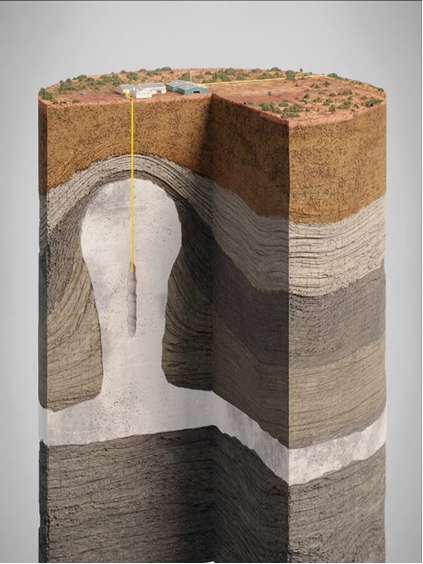

Such a solution, Simon Currie, Energy Estate principle and co-founder, says is vital for New South Wales, since the state doesn’t have any salt caverns or depleted oil and gas, which have also been floated as a potential place for hydrogen storage.

Image: Abergeldie Complex Infrastructure

Hydrogen storage isn’t a simple task – the molecule is small and volatile – but without it, projects like Energy Estate’s proposed Hunter Hydrogen Network simply aren’t secure investment decisions.

“The whole discussion now is basically an energy security discussion,” Currie tells pv magazine Australia. “We need to have lots of security on the production side, and we need to have lots of security along the midstream.”

In hydrogen projects, storage is especially vital because to make ammonia and other green hydrogen derivatives, you need a baseload power source so the plants can run uninterrupted 24/7. How to achieve that, Currie says, is a “both/and” scenario.

That is, you need lots of electrical storage to power the facility – be it in the form of pumped hydro, batteries, concentrated solar thermal power (CSP) – and you also need hydrogen storage so you have a “large buffer sitting on the midstream side of it.” The stored hydrogen then becomes a backstop for when variable sources like wind and solar aren’t available, and pumped hydro or batteries are depleted.

In terms of the types of storage, Currie thinks it all has a place – from iron air batteries and CSP. “We need everything.”

And we need it – or at least need to start building it – now. In his eyes, for Energy Estate’s 30 GW portfolio and pipeline of large-scale projects to be truly viable, storage is key.

Image: Geoscience

Currie is on something of a mission to “Make Australia Make Again” – donning the MAGA revision as a shirt during his panels at All Energy. His goal is to see manufacturing done in Australia, specifically renewable manufacturing. Like others, he points out that Australia missed the chance to produce the solar technology first developed at the University of New South Wales. “We lost first wave, so how does Australia catch the next wave?”

To see this vision come together, Currie has been assembling a big base of partners and other players, saying that when it comes to buying locally manufactured products and services “we’ll always put our money where our mouth is.”

Hunter Hydrogen Network

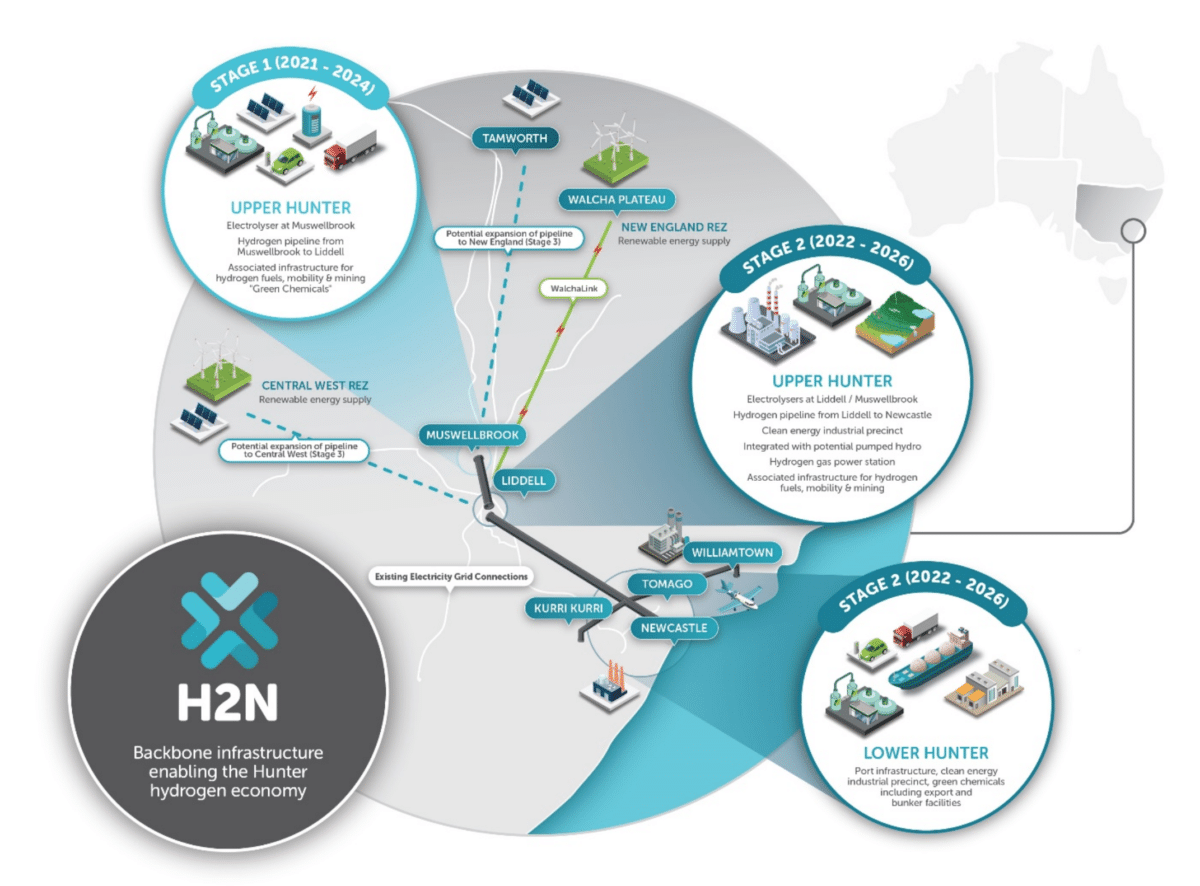

The first project Energy Estate and Abergeldie will be looking at together is the proposed 1.6 GW Hunter Hydrogen Network, or H2N – a proposal Currie describes as more of a “ecosystem” than project.

Image: Energy Estate / H2N

It is being jointly developed by Energy Estate and its partner Japan’s Eurus Energy – itself a joint venture between Toyota Tsusho Corporation and Tokyo Electric Power Company. H2N is in the early stages, having only completed initial scoping. Currie says the project is looking to go through feasibility and development “as soon as possible” and is hoping to deliver the operation project in the mid to late 2020s.

The project is seeking to become Australia’s first “hydrogen valley” and will involve large-scale electrolysers in the Upper Hunter and a 120km dedicated hydrogen pipeline through the Hunter Valley.

The Hunter Valley is currently one of Australia’s major energy hubs but its future looks unsteady given its generation facilities, the coal-fired Eraring, Bayswater and Liddell Power Plants, are scheduled to close in the coming decade.

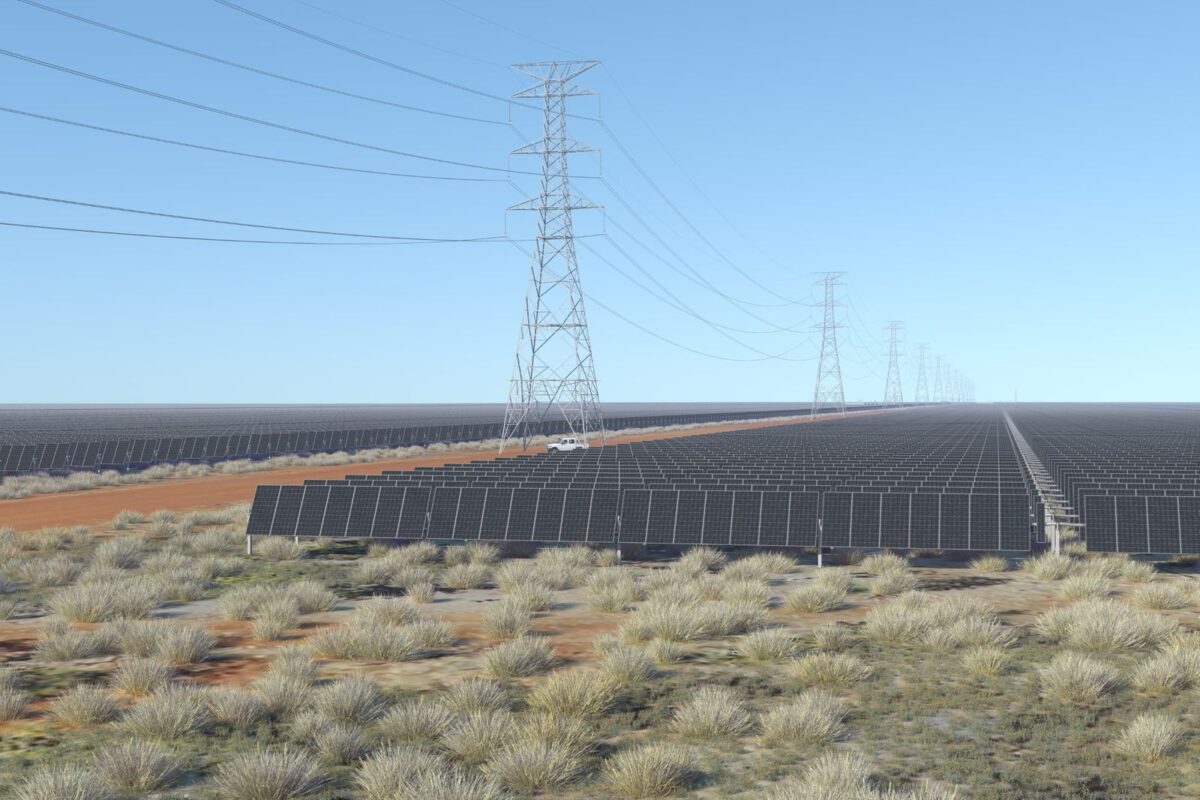

Image: Nick Pitsas/CSIRO

With all this energy and export infrastructure and local workforce, the region is an obvious choice – and is set to become – a major clean energy hub for NSW. The issue there, Currie says, is that for the amount of energy needed, the transmission requirements are huge. And in the populated area, there just aren’t a huge amount of options for 80 to 100 metre wide easements to get bulk electricity transported.

Thus, the proposal for a shared, dedicated hydrogen pipeline would connect the Port of Newcastle and other “strategic locations” in the Hunter.

If you look at what’s happening in Europe, Currie says, the Europe Hydrogen Backbone – a proposed network of pipelines – is getting huge momentum because “we’ve got to understand the math.”

Currently the globe transports more energy as gas than electricity, he says, “because it’s an easier transfer medium for bulk.”

Which is why in Currie’s eyes, the Hunter needs a hydrogen pipeline – common infrastructure that is big enough and ready to go when the projects come into operation. Or to use Currie’s words, it’s about building the tracks at the same time as the train.

“We have the opportunity here to develop projects where they need to be developed, not just where there was stuff in the ground,” Currie says. Oil, gas, mining projects are inextricably linked to certain locations, “but [renewable projects] can actually go and develop in Kurri Kurri, where they used to have a smelter, where they need investment.”

Currie describes the Hunter Valley as the “perfect ecosystem” for projects like H2N. “If we’ve got offshore wind, given what we want to do around clean manufacturing, then we going to be using the hydrogen in a loop – just like they are proposing in the Netherlands.”

For that to come to fruition though, infrastructure is needed first. “You need to go early with infrastructure or else nothing will be built, people won’t come. They’ll go other places in the world,” Currie says.

“If we want to be serious about replacing the coal, keeping the lights on, attracting new industry and being an exporter, then NSW needs to look at what Queensland is doing.”

Hydrogen offtakers

In terms of who will use the hydrogen, Currie sees a lot of potential. Obviously there’s manufacturing and export, but he’s quick to point out that while ammonia export might be a component of H2N, it isn’t the sole focus.

The other obvious use for hydrogen is as a fuel ,such as e-methanol for shipping. Methanol – CH3OH – is four parts hydrogen, one part oxygen and one part carbon, and while he says the carbon component has had people running scared, the makeup holds clear advantages over, say, ammonia because it’s something we use and can produce today.

Fortescue Future Industries (FFI)

“The technology exists to do this,” he says. Liquid hydrogen isn’t something we haven’t done at scale, but methanol is. “It’s not a difficult process [to make],” Currie says, nothing there are multiple companies doing methanation.

The demand for e-methanol, Currie believes, is coming far quicker than trying to create demand for hydrogen trucks. While NSW has committed to deploying hydrogen buses, he thinks only a small portion of demand will come from the local mobility sector – though it remains a key offtake market.

Other markets, he says, include sustainable aviation fuels or SAFs and other biofuels. Customers, he says, are already demanding these products – noting the primary producer in Singapore is well over subscribed.

“We’ve clearly got a supply chain rip.”

Aviation H2

He disagrees that most of the market for hydrogen is still far away – the issue is more that we don’t have the product.

Other possible applications for Currie include high industrial heating in places where electrification doesn’t suffice. Another option is fuel cell passenger trains – something being pursued in Germany.

Energy Estate is also talking about liquid electric gas (LEG). Since lots of Hunter runs on LPG, Currie believes there is a market for bottling a propane butane substitute.

Finally, Kurri Kurri is just “down the road,” Currie says. The controversial gas peaker pushed through by the former Coalition government is something Labor says it will move ahead with but make hydrogen-ready.

“There is no transition without storage,” Currie said finally.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

2 comments

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.