This article follows on from part one, which outlined Australia’s cybersecurity measures and vulnerabilities within the distributed energy resources (DER) ecosystem.

What becomes possible within a newly designed energy system is difficult to predict – and so exactly could happen to these systems in a cyberattack involves an element of imagination.

What is certain is that as new technologies emerge, so too do new potential attack surfaces. “There’s probably truth is what everyone is saying, from people that say ‘you shouldn’t worry about it,’ all the way through to, ‘it’s the biggest threat since cybersecurity was invented,’” Wattwatcher’s Chief Innovation Officer, Grace Young, told pv magazine Australia.

“Does it need the kind of lockdown ‘we shouldn’t do anything’ kind of mentality we sometimes see? No. But we do need to put measures in place,” she added.

Image: ARENA

The implications of control devices

In Young’s eyes, one of the most consequential changes in Australia’s DER cybersecurity landscape is the proliferation of devices capable of controlling residential energy systems, like rooftop solar. As noted in part one, the inverters of new solar systems in South Australia will be required to have software capable of dynamically controlling household solar exports from July 1. That is, the inverters will receive instructions based on network conditions and will adjust system output accordingly.

Victoria will introduce a similar mandate from March 2024, and Western Australia is also travelling this path. Queensland has also mandated a form of solar export control, though its technology choice appears to remain more of a blunt switch off tool like that already imposed in other states.

Given the success of South Australian trials in dynamic exports, the mandates have largely been welcomed and are expected to significantly improve overall solar export capacities.

Image: SAPN

Greater control, however, brings with it greater consequences should that control fall into the hands of a nefarious player. “My understanding is that if they were controlled in a certain way, they could certainly cause grid instability, knocking out blocks, critical infrastructure, all kinds of different things,” Young said.

To be clear – these kinds of consequences could be possible only when control devices are widespread, which is not the case today. Young estimates Australia only hosts a small number of control devices at the moment, perhaps a couple of thousand.

“As we talk today, it is not a massive threat,” she said. But in the next year as these mandates come into force, “then we’ve now got three states where every single solar system that has been installed is controllable. Suddenly the threat is much larger.”

“In about two to three years I think there will be a critical mass [of controllable systems].” If Australia roughly installs around 350,000 rooftop solar systems per year, depending on how many states introduce control mandates, this could see Australia have anywhere from 750,000 to over a million controllable systems installed within three years. “So we are talking about a massive increase in controlled devices just looking purely at solar,” Young said.

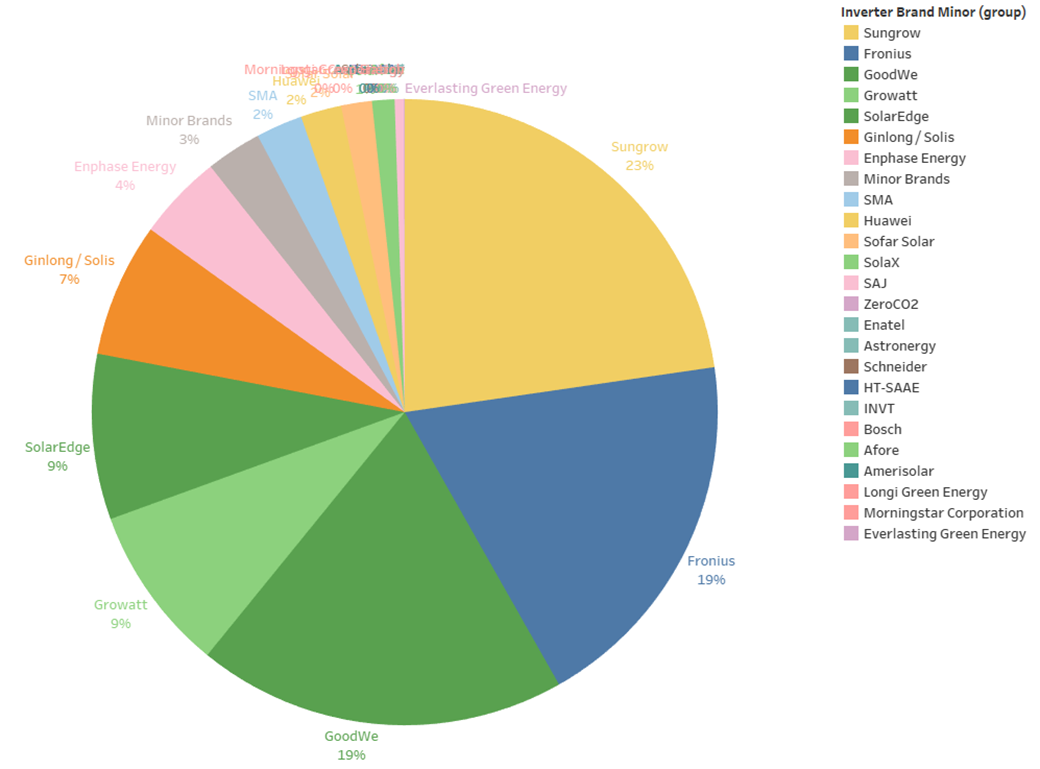

Image: Sunwiz

“In an event where we are wanting to curtail solar and somebody blocks that signal – that could cause grid disruptions and all kinds of issues,” she added. This could also permanently damage critical grid infrastructure, as well as household appliances.

Then there is the possibility of a wide-scale takeover of a raft of control devices to create grid instability, potentially leading to blackouts which could range anywhere from annoying and brief to something more serious.

“What if it’s more targeted and you’ve got nefarious players involved? What if there are other attacks going on at the same time?” Young questioned.

Young also noted neighbourhood or community batteries are rapidly connecting to Australia’s grid, used as a tool to control frequency and voltage and maintain grid stability. “What happens if someone turns that against the grid and uses that to disrupt the grid? These are really serious problems.”

“I can see it becoming quite a serious threat in certain contexts and circumstances if it was done nefariously and, therefore, yes we absolutely have to take it seriously.”

Image: Ausgrid

On the individual level, nefarious control of these devices could cause big disruptions for households in the form of ‘denial of service’ attacks. That is, electricity access and hot water systems could be disrupted and, if the house was a smart home, it could impact a whole range of appliances and other devices. “Is it more a nuisance or serious threat? I don’t know if we can say that. There are probably really legitimate threats in amongst all of that,” Young said.

“The solution is not to not remotely control [DER systems]… but certainly some security is necessary to ensure the information and control remains in the right actor’s hands,” Sunwiz founder and managing director, Wawrick Johnston, told pv magazine Australia.

Data hack consequences

Johnston also pointed to the potential consequences in the event of the considerably more likely event of a data hack.

Data hacks are commonplace today, and when it comes to energy data very particular things can be exposed. That is, energy data reveals when someone is at home and likely also how many people are in a household at any given time.

Devices should take measures to de-identify this data, Young noted. “When it is de-identified data and you can’t trace it back to a household or a premises, it is far less threat as to the exposure of that information.”

“So there are risks associated specifically with energy data and its exposure, but we feel at a general level, they are quite manageable and fairly low risk when you compare them against things like control mechanisms,” she added.

Cyberattacks could easily go unnoticed

In its report on the cybersecurity findings from DER marketplace demonstration ProjectEDGE, the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) flags that cyberattacks in the DER space could easily go unnoticed.

“The DER marketplace is designed to have bi-directional flow of information with each single entity having significant amount of customer and operational data at a given point in time… Lack of consolidated visibility over malicious activity and security incidents across the DER Marketplace, could lead to such activity going unnoticed for a long period of time which could affect the confidentiality and availability of data across the DER Marketplace,” the report says.

AEMO also notes, “due to the interconnected-ness of the marketplace, a compromise of a single entity could have significant impacts across the DER marketplace.”

As an antidote, AEMO suggests far greater testing of DER devices and systems, risk detection processes and recovery processes, to name a few.

Grace Young will present the talk ‘A real-time marketplace for energy data: How do we strike a workable balance between open, proprietary, industry, customer, private and secure?‘ at EnergyNext in Sydney on July 19, 2023.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

See this talk from Germany:

https://media.ccc.de/v/37c3-11810-decentralized_energy_production_green_future_or_cybersecurity_nightmare