By the end of 2024, Western Australia’s Minister for Mines and Energy, Bill Johnston, says the state will account for 10% of the world’s lithium hydroxide demand. By 2028, that figure is expected hit 20%, as planned refineries complete commissioning.

Building on that, Matt Dusci, acting CEO of miner-cum-critical materials processor IGO, says by 2030, Australia will be producing approximately the same amount of lithium hydroxide as China does today.

The path there, however, is not easy. Speaking at the WA Renewables and Critical Minerals Superpower Summit held in Perth on Monday, Dusci described the shift from ore exporter to refined material exporter alone as a “astronomical jump for us [Australia].”

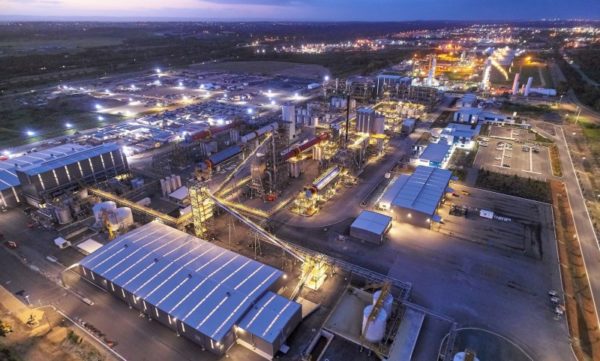

In 2022, IGO and its joint venture partner Tianqi Lithium Corporation from China claimed to produce Australia’s first commercial quantities of battery-grade lithium hydroxide at its Kwinana Lithium Hydroxide Refinery. Meanwhile, in April the company announced plans for another facility, this time to produce precursor material for cathodes in lithium-ion batteries alongside billionaire Andrew Forrest’s Wyloo Metals.

Image: TLEA

This is to say, IGO has a unique vantage point, having gone through the process of building a critical minerals processing plant in Australia as well as planning a higher value precursor plant – an approach which is increasingly being touted as the nation’s path to staying economically relevant in the global energy transition.

Dusci described the process as “incredibly challenging here.”

“Yes, we can compete. We can compete on operating cost, we can compete on a safe and reliance jurisdiction, we can compete on ESG, we can compete when it comes to having a true cost on carbon when producing. Where we struggle is capital. Capital cost is a lot cheaper [elsewhere].”

Dusci’s fellow panelists Tim Buckley, Director of Climate Energy Finance; Cameron Perks, Principal Analyst at Benchmark Mineral Intelligence; Mark Urbani, Founder of Renewable Metals; Joanna Kay, General Manager of Zero Carbon Hydrogen Australia at the Smart Energy Council; and Kirk McDonald, Project Manager at Supercharge Australia, all pointed towards challenges with the flow of capital in Australia in one form or another.

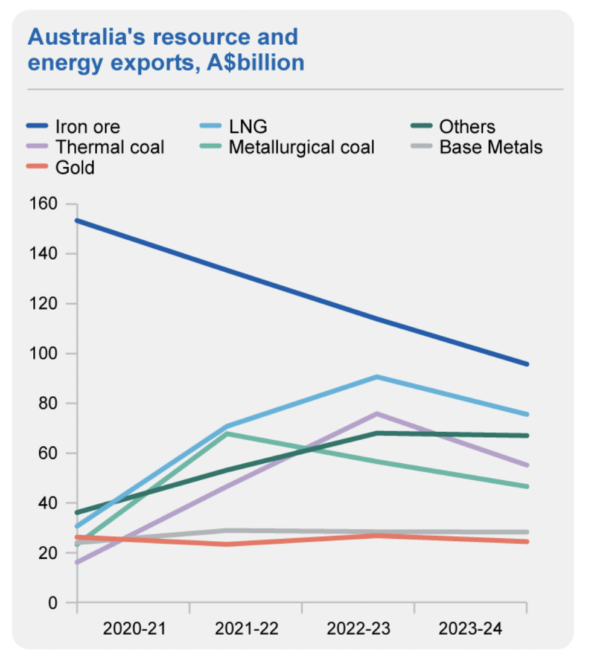

Image: Australian government, under International Licence

CC BY 4.0

Part of the issue Dusci sees with securing capital comes down to the fact that refining critical minerals and processing materials is a new industry in Australia, so it is classed as a risky venture. He pointed out that in counties like Korea and China, where these types of industrial ecosystems are well established, such barriers are far more easily overcome.

To that end, the cost for Albemarle, a US giant which is also seeking to process lithium in Australia, to set up its refinery in Australia was estimated by Cameron Perks of reporting agency Benchmark Mineral Intelligence to be twice as expensive as it would be in China.

Perks also pointed to China’s Tianqi, which he said had tried to replicate its successful Chinese plant model in Kwinana, Western Australia with little success due to the significant regulatory differences between the two countries, and the lack of expertise here.*

Coming back to Monday’s panel, Dusci’s view is that Australian governments need to step in to offset some of the risk associated with the nascent industry. As an audience member pointed out, most of the countries in, or moving into, this space have been heavily subsidised or supported by their governments, including China, Korea, Japan, and increasingly the US and Europe.

The level of support being offered by international governments at the moment is to such a degree that finance analyst Tim Buckley said the market could really no longer be classed as “free.”

This, Dusci said, throws up another huge barrier for Australia’s prospects. “We can definitely get over some of the challenges in the free market. We can’t compete in deploying capital in Western Australia or Australia if it isn’t a free market and there are other incentives that attract that capital elsewhere.”

Can we manufacture batteries in Australia?

Given the challenges that come with just refining, is it plausible for Australia to even pursue actual battery manufacturing, panel chair James Choi questioned.

For something like the electric vehicle (EV) market, battery manufacturing will be done near to where the cars are actually manufactured, Dusci said. The advantages of this hub type of model were echoed by other panelists. (In the Queensland government’s critical mineral strategy, released on Tuesday, it appears to be following a zoned model too.)

Image: ESS Inc.

“The exception will be static storage,” Dusci added. “Static storage is another area where Australia can play.” Unlike the lithium-based batteries used in transport, the shape and chemistries of stationary storage or grid-scale batteries is still being decided. That is, there are a number of viable looking technologies vying to gain dominance, and it is still not clear what will come out on top.

Buckley of Climate Energy Finance pointed out Australia could also have an opportunity when it comes to heavy haulage electric trucks, since as a nation we command much of the market via our mining industry. “In heavy haulage vehicles, Australia is number two,” he said.

Perks’ view was less optimistic. “Who actually knows how to build a battery plant in Australia?” he questioned.

For Buckley, the way to set up the industry here would be through deep partnerships with Korean, Chinese or other countries with established battery manufacturers.

“But can you physically bring the people here to build the plant and ramp it up?” Perks responded.

“We are five or 10 years behind on that expertise. Let’s not pretend like Korea or Japan or China don’t have far more experienced engineers in this area. But we have the best miners in the world, and we’re going to have the best renewables in the world,” Buckley said.

Here Perks again pointed to Tianqi’s difficulties finding the necessary labour force in Australia to realise its vision.*

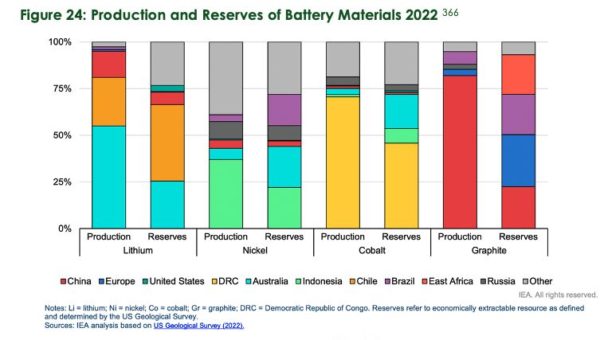

Image: Accenture

Utter lack of skilled labour

This brought the discussion to a crucial junction: Australia’s acute lack of people to actually carry out these projects.

“We simply won’t have the labour force or the skills to build these new industries,” James Choi said. “So there needs to be a policy response to acknowledge the fact we either need to nurture the skillsets here in Australia… and if we can’t build the skillsets here in Australia, we have to acknowledge that we do have to have more flexible work and immigration policies to allow skilled workers to build these new industries.”

“If we want to have a hydrogen industry, if we want to battery industry, I think we need to have a sensible discussion about skilled work in take in Australia without inflaming the political dynamics,” he added.

Again, this point was echoed across the panel. As Buckley pointed out, the global energy transition is a race and the rest of the world is treating it as such. Part of that race is about securing expertise. Australia isn’t the only country needing more engineers and other skilled workers – and other countries seem well ahead in recognising this.

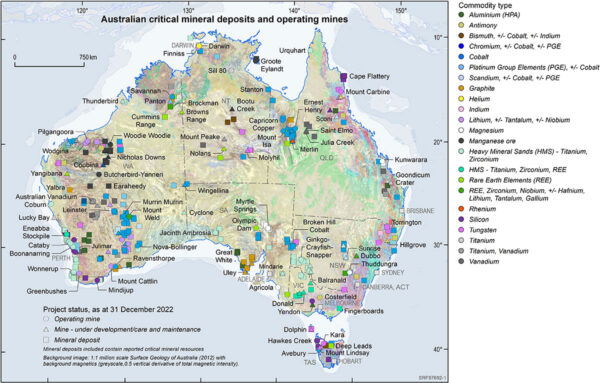

Image: Queensland government

Australia is also losing its entrepreneurs and innovations, Kirk McDonald of Supercharge Australia, which works with startups, pointed out. “The money is coming thick and fast for them to leave, for them to go overseas,” he said. If the “brain drain” phenomenon was once limited to countries with low GDPs, it is now coming for countries like Australia which continue to lack boldness and ambition in its future focus.

What should be included in the government’s upcoming ‘Australian Made Battery Plan’?

With the Australian federal government currently developing an ‘Australian Made Battery Plan’, Choi asked panelists what they each thought would be most helpful to overcome the outlined challenges.

Tim Buckley responded: “I think we should phase out cap and diesel fuel rebates and so we stop creating a headwind for the option of electrification, and then redeploy that capital back into investing for the future.” He noted that the Australian National Audit office in 1996 actually described this policy as a “counter productive strategy,” and Buckley urged governments to finally take their own pertinent advice.

For Joanna Kay, the most important step is to rethink skilled migration. “I’ve seen countries like India, for example, really eagerly seeking those Australian resources, so I’ve seen it on the other side, and they’ve been able to really actively engage in and have those JVs. There’s no reason why we can’t do that. We have to be competitive… we need the man or woman power on the ground to get it done.”

For Dusci, it came down to developing industrial hubs to deal with refining and manufacturing plants, as well as incentivising industries to deal with waste streams. “But ultimately, [we need to] create an environment where government does share some of the risk.”

Renewables Metal’s founder Mark Urbani said we need to start looking now at incentivising consumers and industry to recycle batteries – which are a valuable source of critical minerals – as well as disincentivizing companies from exporting only the lowest possible derivatives of materials.

McDonald’s message was clear: we need more capital. Specifically, governments need to become far less skittish about investing in the future and recognise what is at stake. “We need to make batteries for our own security purposes,” he said. What to invest in our country’s future should not be an ‘if’ but a question of how much, he said.

Image: Geoscience Australia

* Article amended on June 28 to correct a misquote of Perks. Pv magazine previously understood Perks as referring to TNG (now named Tivan), but he had in fact said Tianqi.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

The perennial problem in Australia: getting its act together as a well resourced national team to compete internationally. The points based immigration system provides the flexibility to adjust immigration by skill sets to meet the demands of critical minerals. Why is it not happening?