European Union innovation body EIT InnoEnergy, and recruiter Manpower, have joined forces to provide tailor-made training packages for companies in European net zero sectors, including the battery, green hydrogen, PV manufacturing, and wind industries. This and other much-needed training and recruitment activity for these rapidly expanding industries face structural difficulties deeply embedded in European education and migration systems.

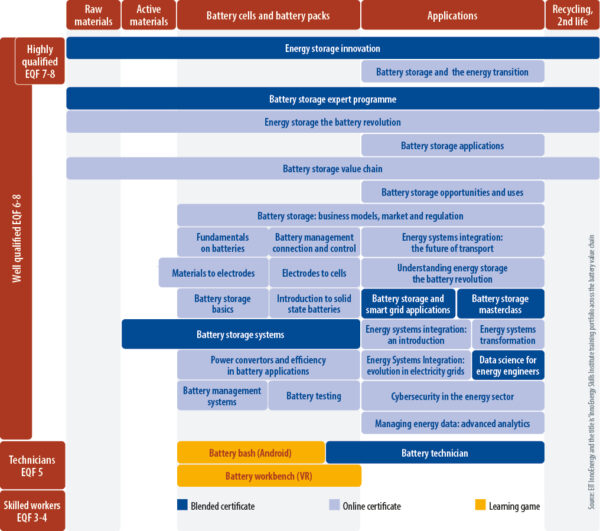

In December 2023, the InnoEnergy Skills Institute, part of EIT InnoEnergy set up to address the skills gap, hit the milestone of 50,000 participants in its training courses, which are designed to meet the personnel requirements of the European Union’s energy transition. The institute has a mandate from the European Commission to upskill the estimated 800,000 workers that will be required for Europe’s battery industry by 2025.

Under the new partnership, Manpower, the third-largest staffing firm in the world, will provide guidance and connection between companies that are recruiting and the courses offered by InnoEnergy. The courses are designed to encompass an agile, modular approach to training to deliver adaptable, customizable courses and programs that meet specific needs regardless of business location, size, or technology.

Flexibility

While the approach of Manpower and the InnoEnergy Skills Institute is designed to be flexible, the scale of the workforce challenge posed by the global energy transition is formidable.

“I think we highly underestimate what re-shoring industry and manufacturing to Europe means, in terms of workforce,” said Oana Penu, the director of the InnoEnergy Skills Institute. She noted that the World Economic Forum anticipates that 18 million jobs will be created globally in net zero industry – in green hydrogen, solar, and battery project realization and component production, by 2030.

At aerospace, automotive, and commercial vehicle grouping SAE International, in the USA, Frank Menchaca is the president of Sustainable Mobility Solutions, an innovation unit working on a non-profit basis with government and industry to meet the challenges of skills training for emerging clean technology industries.

“I think, at least in the [United] States, this is the first time we’ve had industrial policy, probably since the 1950s when the Eisenhower administration decided it wanted to build an entire infrastructure of highways,” said Menchaca, speaking about the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). “We’ve done a good job of articulating industrial policy. We are not doing as well articulating educational policy. Part of that is that, in the United States, education policy is a matter of state rather than federal authority.”

Cross-border alignment

The European Union faces a similar challenge. European member states are responsible for education policy. In terms of reskilling programs for adult education, efforts are further localized and are primarily the responsibility of municipal and local authorities.

The development of cross-border skill and qualification acquisition for employees is also a non-trivial challenge. While extractive industries have skills standards that were internationalized some decades ago, enabling worker mobility across the globe, the same cannot be said of the skillsets required in cleantech industries. Even within Europe, skills standards are not unified.

Henning Ehrenstein, the head of skills, services and professions at the European Commission, pointed to electrical trades as an example of this challenge. “If you talk about the electricians that are key for a number of these technologies, they’re regulated differently in every member state,” he said. “And it has been, I think, 20 years that we’re trying to convince member states to unify that regulation a bit. But I think the political tide is shifting, and I think we’ll have more success, going forward.”

Market matters

A qualified workforce is one piece of the puzzle but employment market dynamics present another challenge. Studies show that, in many respects, 2024 will remain an employee’s market. SAE’s Menchaca said that skilled workers “are the key to everything and have leverage over us in ways that we haven’t even begun to understand.”

That dynamic presents a sizeable challenge to renewable energy companies themselves. Riccardo Barberis, regional president for Northern Europe at ManpowerGroup, explained that growing companies can become stuck if they leave strategizing on recruitment too late.

“We are not, any more, in a situation in which you first think about the facility, then think about the raw material cost, then think about the supply chain, and then, at the end, about the human capital,” said Barberis. For companies with that prioritization, he can only add, “good luck.”

Companies looking to scale their renewable energy businesses will have to look to their future labor needs at the outset. On one hand, that means companies thinking ahead. On the other, it means that skilling programs must be quick, flexible, and tailored to prospective employee needs.

Larger, macroeconomic, trends are exacerbating the problem of an urgent need for young workers. Manpower’s Barberis said, “There are some structural changes in the labor market for the future that are already shaping our reality. And then green transformation arrives, accelerating all those aspects and showing even more clearly how much is the gap between what the companies need and what the labor market can offer.” He said that of the 70% of companies that say they want to invest in green skills, 94% report difficulty finding workers.

Blue and white

Not all employees in the solar and energy storage industries are alike. Both blue- and white-collar workers are required. Oana Penu, from the InnoEnergy Skills Institute, set out the dynamic with the example of a hypothetical gigafactory.

“In the beginning, in the first three to five years of every gigafactory, you need between a hundred and a thousand people,” she said. “Most of these people are white-collar workers because they need to put the processes in place; they need to set up the basics. They need to test, they need to do the research and so on. That ratio changes when the production starts – to 20% white-collar workers and 80% blue-collar workers. Then the challenge becomes: where to source these blue-collar workers?”

In terms of blue-collar staff, there are geographical shifts in Europe with some regions in decline while, in others, many new jobs are being created. “You have a whole ecosystem of suppliers around the big OEMs [original equipment manufacturers] in Europe, where tens of thousands of jobs are directly tied to the combustion engine,” said Penu. “If the mobility transition isn’t handled well, this can lead to entire regions going from being very prosperous into being plagued by unemployment. Then you have emerging industrial areas which need these workers. For instance, in Sweden, in Germany, or in the north of France.”

To help address this shift, the skills institute is endeavoring to design programs that provide credentials and skills that enable workers to be agile in taking up new opportunities. This can include training that can provide the opportunity to work in other countries because it is recognized at a European level and in other languages.

White-collar workers are a different story. Highly educated people often speak English and have fewer problems with mobility. Penu says here the challenge is “to find the right work-life balance and the right status or payroll situation.” Companies must “create a very attractive package,” meaning social infrastructure for skilled workers, their partners, and families – including good schools, medical services, and cultural activities.

Mobility and labor market access appear to be key elements. The European Commission’s Ehrenstein advocates for more migration-friendly policies to facilitate worker mobility within Europe and access to both skilled and less-skilled younger workers from outside the bloc.

Penu, from the InnoEnergy Skills Institute, said, “I am hoping that at some point somebody will have a vision for Europe where we structure visas for work, [so] we really attract talent in a dignified manner.”

However, reports indicate that politicians are not responding to the urgent need for workers. Politicians are saying that the last thing they can do politically at the moment is sell more immigration, more mobility, and more foreigners coming into their respective countries – those policies simply won’t get them re-elected. This dynamic is standing in the way of solid policymaking.

Within the European community, an untapped group of highly skilled workers in relevant fields has failed to receive attention from recruiters. While Western Europe has a low number of women in science and engineering skills, in some Eastern European countries the number of female graduates equals and even exceeds the cohort of male counterparts. Those female graduates can have problems finding jobs after graduating because of job environments that may be hostile to women. In Western Europe, the number of female students in science, technology, engineering and math fields accounts for around 30% of graduates, compared to more than 50% in some former Eastern bloc countries.

A new approach

There are practical solutions available to break down embedded and unhelpful barriers. SAE’s Menchaca said, “I think it’s incumbent on industry to take an active role in this, to recruit people decidedly from outside of privileged areas, to recruit people who don’t go to elite schools, and to offer support – through foundations and through corporate investment in kindergarten through primary education – specifically for people from disadvantaged communities. Because innovation is giving people an understanding that these opportunities are available to them. Corporations have to take a responsibility to do that while government has to sort itself out as well.”

Manpower, despite its name, has demonstrated an ability to enable workforce access outside of traditional demographics. Barberis illustrates the point with a challenge Manpower encountered in the United Kingdom. When confronted with an urgent need for truck drivers, the usual candidates were simply not responding, or available. “But why is it considered a job for men?” said Barberis. “[We thought] ‘let’s do a driver academy for women’, [and] it was a great success. And now we have hundreds of women drivers in the UK.”

If a company called Manpower can break down barriers for women in this way, there are ways in which Europe can address the lack of workforce mobility and access to the renewable energy industry both within and outside its borders. The incentives are high: no amount of technology and funding will bring the growth needed in the solar and energy storage industries if there are not the people and skills to make it all work.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.