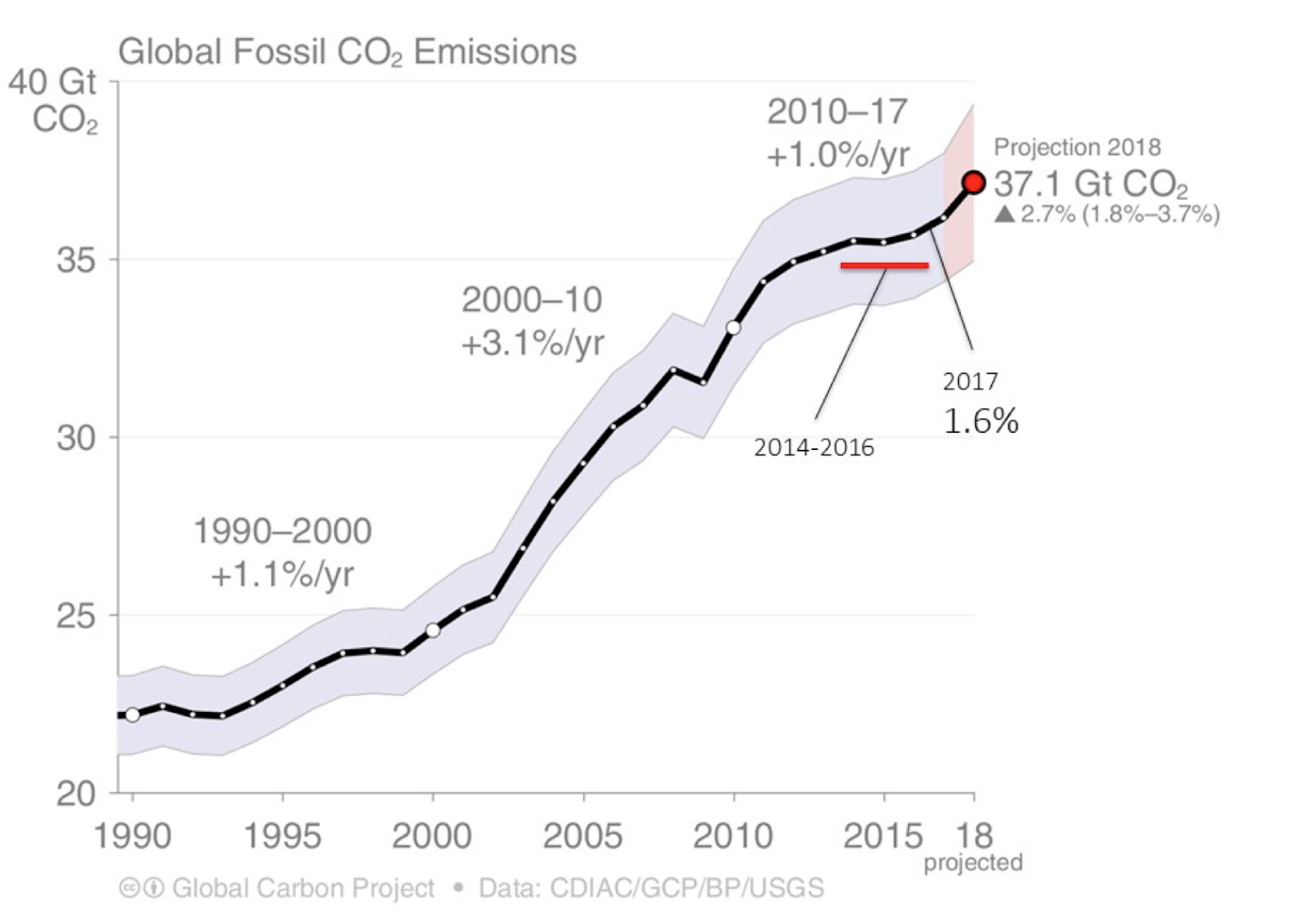

After three years of virtually flat global emissions growth to the end of 2016, The Global Carbon Project, hosted in Australia by the CSIRO, has recorded the second consecutive year of growth in CO2 emissions.

Where 2017 saw fossil CO2 emissions increase by 1.6%, 2018 confirms a spike in emissions with an even higher increase of 2.7%. “The biggest surprise in the data was that the gap between what we need to do and what we’re doing is growing,” says Pep Canadell, CSIRO Chief Research Scientist, and director of the Global Carbon Project.

Graphic: Global Carbon Project

The cause of increased emissions, according to the Project paper, Global energy growth is outpacing decarbonization, is the otherwise holy grail of economic growth, which has in turn driven greater electricity consumption.

For example, in China, increases in iron, steel, aluminium and cement production have burned through enough natural gas, oil, and coal to contribute to the projected 4.7% increase in emissions for the country this year.

One bright spot is that at least 19 countries — including Barbados, France, the UK, US and Uzbekistan (but not including Australia) — have achieved significant declines in CO2 emissions in the presence of continued economic growth over the past 10 years. However, these beacons on the road to mitigating climate change could be toppled by ongoing hikes in emissions.

Clearing peak emissions for a true downhill run to greener pastures, stable sea levels, and thriving coral reefs — to name just a few iconic benefits of arresting global temperature rises — depends on accelerating transition from fossil fuels to renewables.

In the renewables sector, solar PV currently shows the greatest promise for continued rapid growth, and the supply of exponentially greater volumes of electricity into the sector.

This is in large part due to its potential for development that will increase its conversion efficiency and also the efficient use of resources in solar PV manufacturing.

In Australia, solar PV has transformed the household energy landscape, with two million households now living under solar panels according to figures released by the Clean Energy Council on 3 December. The incentive to invest in rooftop solar generation has been the potential savings to consumers who have been hit by increases of 117% in the cost of electricity over the past decade.

“Homes with rooftop solar installed are saving an average of about $540 per year on their electricity bills,” said Kane Thornton, Chief Executive of the Clean Energy Council this week.

Such cost benefits must now be translated on a large scale to the commercial-industrial sector in Australia and globally, in order to multiply the impact of economic gain alongside carbon emissions saved.

Putting the light into industry

Solar PV provides “very good” opportunities for light industry and commercial enterprises, says Professor Frank Jotzo, Director of the Centre for Climate Economics and Policy at the Australian National University’s Crawford School of Public Policy. Consumption patterns are perfectly placed to take advantage of daytime solar generation even in the absence of significant investment in battery systems.

“In the shopping centre or factory, most of the electricity consumption takes place during the day, for lighting and cooling and other processes, and that’s where solar panels on the roofs of commercial buildings make a lot of sense,” says Jotzo.

The choice between rooftop solar panels and other emerging on-building installations, and taking out a power purchase agreement (PPA) with a renewable energy provider generating solar or wind power, depends on the size, demand patterns and location of each business, industrial concern or corporate entity.

Among the primary barrier to companies understanding and integrating large-scale renewable energy into their business plans are the complexity of the energy market, high transaction costs and a lack of intimate knowledge of their own energy-use profiles.

Today saw the official launch in Melbourne of the Business Renewables Centre Australia, which is set up to inform, streamline and accelerate corporate purchasing of large-scale renewable energy. “We’ve set a goal of 5 GW by 2030,” said Monica Richter, Senior Manager of the BRC-A, speaking at the Smart Energy Summit this week. “That’s about 20% of New South Wales load, and about 25% of Victorian load.”

Image: pv magazine/Natalie Filatoi

Corporate purchasing power has in turn recently helped to underwrite several renewable-generation projects that might otherwise not have secured finance and investment.

The confectionery company Mars, for example, this year signed a 20-year contract with Total Eren to source the equivalent of the energy needs of its six Australian factories and two offices from the first, 200 MW stage, of Kiamal Solar Farm, due for completion in 2019.

Such deals benefit purchasers while growing the installed renewable base, accelerating the displacement of thermal power generation and reducing emissions.

The cars that ate the Paris Agreement

Solar also shows promise for being the primary generator of electricity to power the global transition to electric- and hydrogen-powered vehicles.

This silent revolution can’t come fast enough, as the data from the Global Carbon Project shows that most of the global rise in carbon dioxide is attributable to “oil in transport and gas in industry”.

In Australia, figures released in June by the Australian Department of Environment and Energy show domestic transport makes up 19% of Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions (having increased over the year to June 2018 by 2.6%).

The Climate Council puts the share generated by cars at around half of that 19% figure. In 2016 it calculated the grams of CO2 emitted by the average Australian car as 250 gCO2/km; emissions of new cars as 184 gCO2/km; and those of electric cars as 6 gCO2/km.

Professor Jotzo says since solar PV is widely expected to be the cheapest source of renewable energy in the future, it will be the economical choice for charging electric vehicles, and for producing hydrogen from electricity.

“Based on current trends, it does look likely that new renewables will eventually grow fast enough for CO2 emissions to fall, even under current policy settings” says Professor David Stern, an energy and environmental economist in the Centre for Applied Macroeconomic Analysis at the Crawford School of Public Policy, in a comment on the Global Carbon Project report.

In the meantime, he adds, “we should expect emissions to rise for the next several years, unless there is another global recession”.

Natalie Filatoff

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.