The Mount Majura Solar Farm site is leased from Mount Majura Winery in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) and will have the capacity to power the equivalent of up to 260 homes, thereby displacing the need for 1,700 tonnes of CO2 to be released by fossil-fuel energy generation.

SolarShare, the community organisation developing Mount Majura, anticipates between 400 and 600 community investors will take part in the co-operative project, with the smallest possible investment set at $500 and the largest at $100,000 per member.

“We’re really pleased to have the kind of structure where we can have hundreds of investors, particularly those people who might rent or live in apartments,” says Lawrence McIntosh, Principal Executive Officer of SolarShare.

Around 30% of Australians are currently excluded from the cost benefits of powering their lives with renewable energy, for reasons such as they rent their home, or they have an unsuitably shaded roof or roof space too small to accommodate viable solar PV generation.

Although SolarShare’s original proposal was for a solar farm of up to 4 MW capacity, it chose to build 1 MW because it allowed the company to take advantage of the ACT Government’s Community Solar initiative and sell its output to the grid for a guaranteed Feed in Tariff of 19.56 cents per kilowatt hour. Profits from the resulting annual revenue of more than $360,000 will be returned to investors.

Steve Blume, President of the Smart Energy Council declares his own shareholder interest in Mount Majura Solar Farm before saying that “$500 is within the realm of investment for a lot of people, and in this case their long-term returns are set, and they’re comfortable returns for a long-term investment.”

Ison estimates there are around 10 community groups across the country currently working up megawatt-scale renewable energy projects. The biggest challenges they face are access to seed funding of between $100,000 and $200,000 to bring projects to an investment-ready stage; negotiating grid connection amid inconsistent regulations and reluctance by distribution network companies to constructively engage in the process; and wrangling the economics of a situation in which all costs including grid connection are more economically proportional to a 15 MW development than to a 1 to 5 MW development.

That said, Ison sees a growing need for mid-scale solar and wind developments at this stage of Australia’s transition to renewable energy sources. “We are going to have significant transmission constraints in the next five to seven years, which is going to make really large-scale renewables projects and their connection to the grid difficult. We need to resolve those issues as soon as possible, but in the meantime here are plenty of sites suited to mid-scale wind and solar farms.”

Compared to large-scale projects, such distributed connection reduces the load at any one point of transmission and is particularly suited to community aspirations for participating in the renewable-energy revolution.

“I think it’s an idea that really catches people’s attention as a different way to deal with energy in our economy, a way of influencing how energy generation impacts our communities and our environment.” says McIntosh.

Ison says both the size of Mount Majura Solar Farm and its government-supported financial offering represents a growing maturity in the Australian community renewable-energy space, the development of which is following that of solar PV in general.

As with rooftop solar, the majority of an estimated 175 community energy projects realised to date have been on a small scale. They include: co-operative power purchase agreements, or ‘bulk buys’; crowdfunding campaigns to install solar on surf-lifesaving clubs and community halls; and communities investing in solar arrays on business rooftops for a guaranteed return, as in the case of Bakers Maison in Sydney.

“For a bunch of reasons,” says Ison, behind-the-meter PV has been most commercial in Australia. We’re only starting to see a really large-scale solar industry burgeoning in the past three or four years. And mid-scale renewable projects, are very, very new.”

The lack of government support for mid-scale renewables is changing with the recognition, driven by organisations such as the Community Power Agency (CPA), that enabling uptake of rooftop solar — and therefore lower electricity bills — for homeowners is inequitable, because it doesn’t include many Australians who most need energy-bill relief.

Lobbying by CPA informed Sustainability Victoria’s Community Power Hub Project to investigate a range of models for community energy; Victorian Labor has initiated an $82 million shared-benefits program, encouraging landlords and tenants to form agreements on installing rooftop solar and distributing financial benefits throughout the property; the NSW Liberal Government has announced a $30 million Regional Community Energy program, expected to open for submissions in February; and the Federal Labor opposition has pledged a $100 million Neighbourhood Renewables Program taking inspiration from Victoria’s Community Power Hubs’ project.

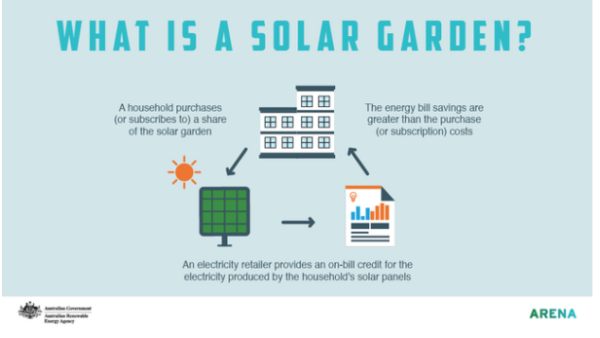

A report released in December by CPA and the UTS Institute for Sustainable Futures under the title Social Access Solar Gardens showed that this model of community-energy participation could, with government support equivalent to that currently offered to household solar installation, save people who can’t install solar on their own rooftops between $290 and $370 on electricity bills each year.

A solar garden is a centralised power station that offers households an opportunity to buy a share of panels and have the generated electricity credited directly to their electricity bills.

“We like the solar gardens idea,” says Ison, “because it can support every kind of locked-out energy user — you don’t need to have access to a sunny roof.” Although a solar garden may use roof space available somewhere in the community, it can also make use of disused or under-utilised land, such as council sites.

SolarShare, now the poster child for a successful mid-scale, government-enabled community-solar project, expects to be fully subscribed with the necessary capital of $2.8 million within months, and to deliver its first power to the grid around the end of October this year.

This flagship project for the community group will be followed, says McIntosh by a number of others, most likely “high on the meter”, says McIntosh. “There are a number of Canberra organisations interested in having a solar farm on their property, and there are a couple of energy users with whom we could secure a power purchase agreement.”

The benefit to participating organisations and businesses goes beyond reducing their carbon footprint, and lowering their electricity bills, says McIntosh. Partnering with a community energy group will increase their local connections and visibility to consumers — “They’ll really benefit from having a community of people with a strong attachment to their organisation,” he says.

McIntosh also mentions that if Canberra is to achieve its ambitious goals of running on 100% renewable energy by 2020, and net zero emissions by 2045, “It will require participation at so many levels of society. Helping people to act, whether it’s at a household scale, a neighbourhood scale or a whole Territory scale, is part of achieving those targets.”

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

3 comments

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.