From pv magazine ISSUE 04 – 2021.

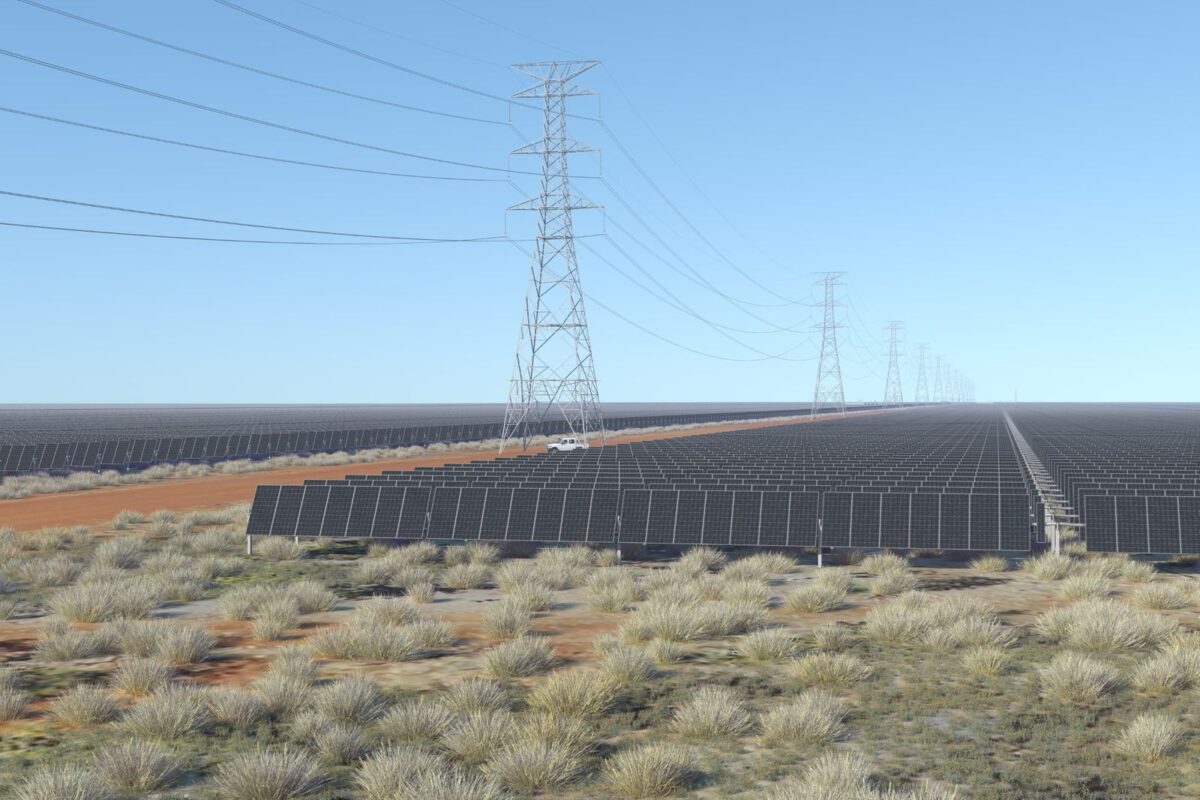

Oil and gas companies are increasingly positioning themselves as allies of renewable energy. Today, fossil fuel companies around the globe are reinventing themselves as purveyors of “energy.” These moves include investing in solar infrastructure, slurping up experienced renewables operators and energy-software innovators, and testing the waters of green hydrogen production.

The greening of extractive industries such as oil, gas and the mining sector is being driven by environmental and sustainability goals (ESG) and commitments to zero-emission targets beyond the mere cost reductions offered by renewable energy. And therein lies the next incredible breaking wave of demand for solar-generated power.

Craig Bearsley, director of energy at infrastructure developer AECOM in Australia and New Zealand, won’t reveal the total he reached in back-of-the-envelope calculations of demand for large-scale solar and wind generation in the coming 10 years, but he says it’s blinding. Both Bearsley and the CEO of the Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA), Darren Miller, say you only have to work backwards from the net-zero dates set by a few global companies to realise that the appetite for clean energy will be insatiable.

In March, Australia’s Fortescue Metals Group (FMG), the fourth-largest iron ore producer in the world, pledged to achieve net-zero by 2030, 10 years earlier than previously planned, and put a preliminary number on its plans to decarbonise its operations and become an exporter of green hydrogen and green ammonia – 300 GW of renewable generation.

Iron awe

At a press conference that put more detail behind FMG’s ambitious plans, Julie Shuttleworth – the CEO of the company’s wholly owned decarbonisation engine, Fortescue Future Industries (FFI) – told pv magazine that the company is “aiming to develop 100 GW to 200 GW here in Australia of renewable energy that will be used to generate green hydrogen, green ammonia and other green industrial products for export.” Australian production will tie in with global projects of a similar capacity, some of which company founder and Chairman Andrew Forrest negotiated when he traveled the world to identify partnerships and potential for green-energy development at the height of the pandemic.

“We see solar playing a significant role in the development of our green energy plan, and we’re already employing large scale solar in our existing iron ore operations,” said FMG CEO Elizabeth Gaines, referring to the 150 MW currently under construction as part of FMG’s hybrid (solar/LNG/battery storage) power facility, Pilbara Energy Connect.

FMG also has an agreement with Alinta Energy to power its Chichester Hub iron ore operations with a hybrid power station incorporating a 60 MW solar installation with Alinta’s Newman 145 MW gas-fired power station and 35 MW/11 MWh battery facility. The Chichester project demonstrated that a complex mining operation could be 100% fuelled by renewable energy in daytime hours, and could displace 1 million litres of diesel fuel per year.

No coal

As of mid-2021, Chichester will also provide renewable energy to generate hydrogen that will fuel 10 FMG coaches used to transport employees. This trial is a forerunner to fuelling other vehicles in the miner’s mobile fleet using hydrogen fuel cells and thereby displacing its 400 to 450 million litres of diesel consumption. FMG has declared a 1-billion-litre annual diesel habit, which in itself will take some solar rollout to replace.

Forrest is not prepared to be more specific about the amount of solar or renewable generation needed to realise the company’s ambitions of powering its (and others’) ships and locomotives with green ammonia; powering electric haul trucks; running drill rigs on green hydrogen fuel cells; and using renewable energy to convert iron ore to green iron at low temperatures – no coal required.

The future-focused FFI is currently developing and trialling these technologies that will contribute to meeting FMG’s 2030 net-zero target. Guidance for expenditure on trials by FFI is AUD 80-100 million ($62-77 million). “We’ll advise the capital investment as projects are endorsed,” said Fortescue CFO Ian Wells.

For one enterprise to go from generating megawatts of solar to hundreds of gigawatts of combined renewables in 10 years would be breathtaking.

‘Energy superpower’

At AECOM, Bearsley believes that companies with near emissions targets and deep pockets will enable Australia to truly capitalise on its unsurpassed combined solar and wind resources. That Australia could become a “green energy superpower” has become a political slogan.

The reality of supplying enough green energy to power Australia’s energy transition, decarbonise its manufacturing, extractive industries and agriculture so that its products qualify for trade across emerging carbon borders, and exporting green energy in the form of hydrogen and ammonia, will require capital, armies of trained renewable-development workforces and sheer drive.

Purveyors of that displaced diesel, of petrol in the face of electric vehicle acceleration, of shipping fuel, must channel that drive in order to meet shareholders’ demands for growth in share value alongside meaningful decarbonisation. Their main goal will be to find new sources of environmentally sustainable revenue. Carbon offsets will have to be part of it, says Bearsley, but they fall into the costs column of any balance sheet, as does carbon capture and storage.

Tony Nunan is Royal Dutch Shell’s EVP of integrated gas in Australia and country chair. He quotes the company’s global target, to become “a net-zero-emissions energy business by 2050,” with that target encompassing emissions from all company operations, and the use of all the energy products sold by Shell.

In 2019, Shell’s direct emissions (Scope 1), as tabled in its Sustainability Report for the year, totalled 70 million tons of CO2 equivalent. Its indirect emissions (Scope 2) came to 10 million tons of CO2 equivalent, while emissions from the use of its refinery and natural gas products hit 576 million tons of CO2 equivalent.

Solar foundation

Shell will have to purchase offsets as part of its strategy – dubbed “Powering Progress” – to meet its zero-carbon target, Nunan told pv magazine. But it also sees solar energy as “a building block in Shell’s power value chain,” Nunan adds. “We are expanding our solar power generation capability by investing in the development and operation of long-term commercial and industrial solar projects … using more solar power at our own sites and building solar farms worldwide.”

In Australia, Shell has acquired a 49% interest in established solar developer ESCO Pacific, which boosts the O&G major’s local clean-energy expertise and allows it to leverage its vast corporate connections to grow a green-energy company in which it has a holding.

Shell also chose Australia as the site of its first industrial-scale solar generator. The 120 MW Gangarri Solar Farm in Queensland (due for completion this year) is being constructed on land that forms part of Shell QGCs fracking operations. QGC’s gas processing facility will be a major offtaker of Gangarri energy, purchased via the grid, reducing its carbon footprint by 300,000 tons a year.

Bearsley sees companies like Shell potentially supplementing their clean energy expertise and revenue streams with ongoing acquisitions, but also increasingly running their own developments. Shell acquired German solar-battery manufacturer sonnen, with manufacturing facilities in Adelaide, in 2019. In the same year, it also bought ERM Power, a leading energy retailer to Australian commercial and industrial customers.

“It could really change our industry for the better,” he says. “We haven’t got enough capable organisations that are bankable, that can attract investment” to meet the coming wave of demand for renewable energy. But “some of those problems disappear once projects are being built by the likes of Shell, which can just finance them itself,” he adds.

Winning combo

As companies with pipeline infrastructure, deep expertise in transporting fuels, and often extensive networks of service stations, oil and gas majors are ideally placed to drive development and distribution of green hydrogen. The technology has a way to go to become commercially viable, but Miller says ARENA modelling has confirmed that an equal mix of co-located solar and wind provides the lowest-cost hydrogen molecule. “We’re pretty fortunate in Australia because our solar-wind combination is the best of anywhere in the world,” he says.

Australian researchers and developers, Miller adds, are striving for the tipping point – the federal government has set a goal named “H2 under $2” (per kilogram). And ARENA will announce the recipients of its $70 million Renewable Hydrogen Deployment Funding Round – intended to help demonstrate promising technologies at scale – in mid-2021. Reaching the tipping point, says Miller, is the hard part, but once there, Australian capability can rapidly harness the country’s natural solar and wind resources and surge to meet demand.

Research firm Frost & Sullivan recently forecast 57% compound annual growth in global green hydrogen production, from 40,000 tons in 2019 to 5.7 million tons in 2030, in response to demand for low-carbon, high-density fuels.

Decarbonisation aims

FMG is an outstanding representative of the decarbonisation ambitions of the resources sector, and Shell is a metaphor for the oil and gas industry. And the next 10 years encompass stretch goals and interim goals for the transition of these behemoths to become monumental users and providers of green energy.

“We’re looking at many hundreds of megawatts and potentially gigawatts of new generation in Australia that can be justified for the hydrogen opportunity alone,” says Miller. “The real opportunity comes from things like upgrading iron ore for green steel production.”

Natalie Filatoff

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.