From pv magazine 05/2022

In February, one of Australia’s biggest rooftop solar players, Infinite Energy, announced it would be shutting its doors, citing “changing sector dynamics.” The company, which was owned by Japanese industrial giant Sumitomo Corp., had offices in every major region, and still said it could not uphold a “sustainable” business model.

The closure was preceded by the voluntary administration of an even bigger commercial rooftop company, Todae Solar, which was widely lauded as one of Australia’s finest solar contractors. After installing systems at Parliament House, Olympic Park and several universities, Todae Solar pointed to the pressures from solar’s uncoordinated surge as compounding the company’s downfall.

Australia easily leads the world in solar per capita, at almost 1 kW per person. But exciting as the solar boom has been, Huon Hoogesteger, founder of Smart Commercial Solar – which operates in the commercial and industrial (C&I) segment – says the industry’s massive growth contained the seeds of its own undoing. “Solar is great, but it’s certainly not something we’re building our future on,” he said.

The flood of solar into Australia, he says, has led to a phenomenon he calls the “solar cliff” – the point at which there is so much solar power in the grid during the day that demand, wholesale prices, and eventually grid stability, begin to collapse.

“If you continuously pump more and more solar into the grid in the middle of the day it leaves no room for any other form of generation,” said Hoogesteger. “And that’s exactly what we’re seeing now.”

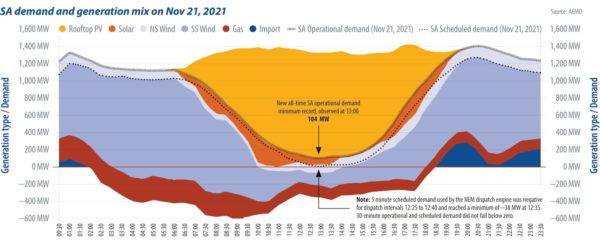

Not only is it driving coal plants out of business, solar is cannibalising itself. In the March 2021 quarter, the state of South Australia (SA) saw average daytime wholesale electricity prices fall below zero. Later that year, the state became the first gigawatt-scale grid in the world to reach zero demand, when distributed generation assets exceeded local load.

Electricity networks in SA now have the capacity to remotely shutdown private rooftop solar systems should their generation threaten grid stability. The state of Western Australia has now enacted the same model, creating a “kill switch” for new systems. “You can’t just produce power and not use it,” said Hoogesteger.

Steve Hoy, CEO of power tracing software company Enosi, agreed. He said that the country needs to be more discerning about what time new renewable assets generate. “Australia has significantly too much solar investment going on for our own grid.” As the lowest-cost form of energy generation, solar obviously has a future, he added. “Let’s use as much of it as we can, but we can’t use it all the time.”

The risks to Australia’s national electricity network are mitigated with the introduction of storage and greater coordination, and self-consumption – though in reality, this is far from a done deal. In the meantime, solar rollouts further undercut their own business case.

Founding Smart Commercial Solar in 2012, Hoogesteger built the company on a marriage between solar and financing, offering his customers systems at no upfront cost with payback via clean energy power purchasing agreements (PPA). The model has been a success, but the clarity of the proposition is waning as the solar-flooded daytime grid prices approach his own PPA pricing. This is compounded by the increasing number and competitiveness of energy offers from retailers.

Profitability is possible

David Leitch, principal at energy market analyst ITK Services, has a slightly different view on solar’s downward pricing pressure. Pointing out that daytime pricing this calendar year has been notably higher than the dire economics of periods in 2021, Leitch described profitability as more river than cliff.

Repeating the financial industry’s mantra: “The cure for high prices is high prices, and the cure for low prices is low prices,” Leitch told pv magazine. “Whatever the price is today, it’s creating a change that will move prices to a different place in the future.”

This move being stimulated in Australia is clearly towards load shifting, precisely where Hoogesteger believes customers will need to head. Corporations are continually committing to 100% renewable energy targets, some as early as 2025, but getting to a true 100% is an unsolved problem.

“How do we meet those needs?” Hoogesteger asked, noting solar tends to generate only around 35% of his customers’ total energy needs. “It’s not going to be with solar panels. It’s going to be something else.”

Given that battery storage systems would need to halve in cost to become “financially sensible” for most of his customers, Hoogesteger said he believes a suite of imperfect and partial solutions are today’s answer, including energy management and energy trading, via demand response, storage, or through virtual power plants (VPPs).

Hoogesteger recently finished designing, and is soon to be installing, a system which included a 5.5 MWh battery, 600 kW solar array, and demand management and response. “So the battery becomes UPS [uninterruptible power supply],” he explained, trading energy in and out of the site, while playing on spot markets and FCAS.

With these shifting dynamics in mind, he believes solar companies in Australia need to rapidly move away from the models they’ve historically used – selling solar as a product – and look towards offering wider solutions. In the bigger picture terms of getting Australia’s grid there, Hoogesteger said the solar cliff issue stands and “deserves some pretty big thinking.”

Wider solutions

These big thoughts are currently being pondered in rooftop solar rich Western Australia, where government bodies have come together to fund an $25 million VPP program called Project Symphony to marry the orchestration of distributed assets for the purpose of physics rather than purely profit.

To this end, Western Australia – which has its own islanded network separated from Australia’s national electricity market – has set up two new markets to consider the needs of the local network. “The interesting thing about Western Australia is they’re looking to a market to try and price those things,” Andrew Mears, founder and CEO of SwitchDin – the company delivering the VPP technology platform for Project Symphony – told pv magazine.

Another novel approach to monetising necessary storage services was put forward in April by the owner of Australia’s largest battery portfolio, French developer Neoen. It struck a deal with the country’s main energy company, AGL, to provide 70 MW/140 MWh of virtual battery capacity from its 100 MW/200 MWh Capital Battery, which is currently under construction in Canberra.

“This offtake will enable AGL to hedge its customer load by virtually charging or discharging the battery at any time over five minute trading intervals,” Neoen said, describing the Australia-first offering as ideally suited to managing the increasing challenges of the solar “duck curve.”

Load shifting

To balance Australia’s growing daily oscillations, new policy drivers are required. “We need to stimulate loads, we need to stimulate electric vehicles markets, we need to stimulate storage markets,” Hoogesteger said. With the federal election on May 21, the country’s future renewable policies remain a point of contention.

If done effectively, such load shifting becomes the solar’s cliff’s antidote – preventing supply overtaking demand, Enosi’s Steve Hoy noted.

If it isn’t done effectively though, Hoogesteger fears solar is at risk of becoming demonised by energy market stakeholders. “If all of this is about being green but we end up with an unstable grid, we’re going to have the reverse effect.”

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

So where are the state & federal policies to help promote the uptake of home solar & batteries while doing the same at the grid level with installing grid scale batteries, or neighborhood scale batteries to manage the influx of solar generated electricity into the grid? This will increase the speed of decarbonizing the grid and allow people lower electricity rates. What’s the issue, other than political will?

Fil, good question, but you already contained the answer in there: political will.

Easily solved with EVs and V2G and home, building heat/cold storage.

Just 1mm EVs is 200GWh, more than all the grid battery storage in the world and that is just Tesla’s EV production in 1 yr.

Australia’s other big need is producing EVs, Heat/cold storage, small wind generators and small CSP for homes to businesses.

Use it, don’t lose it. During the peak hours, after the local batteries are full, turn on the de-salinization plants to turn excess electricity into fresh pure drinking water. At de-sal plants, they turn on very large electric motors to push sea water through semipermeable membranes to extract fresh water. That fresh water can be put into the local municipal water system, bottled or even turned into H2 hydrogen for fuel. Short term storage can be accomplished with batteries, but long-term storage needs to convert the electrical energy into kinetic energy, such as pumping water behind elevated tanks or reservoirs or making Hydrogen from water for fuel cells or burning in conventional fuel power turbines. With more water, Australia can grow and export high value food crops. Until batteries become dirt cheap, use the dirt to grow crops using de-salinization and solar generated electricity to make the water available.