Australian prime minister Anthony Albanese and Indian leader Narendra Modi have met in Sydney to discuss bilateral trade and cooperation in new energy sectors, among other matters.

The pair have agreed to establish an Australia-India Green Hydrogen Taskforce, though details remain scarce. The announcement outlines that the two prime ministers have agreed to the Taskforce’s terms of reference, though precisely what these terms are has not yet been made public.

Prime minister Albanese did, however, say: “the Taskforce will comprise Australian and Indian experts in renewable hydrogen and report to the Australian-Indian Ministerial Energy Dialogue on the opportunities which are there for Australia and India to cooperate in this important area of renewable hydrogen.”

The Taskforce builds on a proposal first made in March at the Australia-India Annual Leaders’ Summit.

The prime ministers have also “identified concrete areas for cooperation and in renewable energy sector,” Indian prime minister Modi said. “We had constructive discussions on strengthening our strategic cooperation in the sectors of mining and critical minerals,” he added.

The South Asia director of the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), Vibhuti Garg, recently outlined how India and Australia can help one another realise their clean energy ambitions by providing supply chain alternatives.

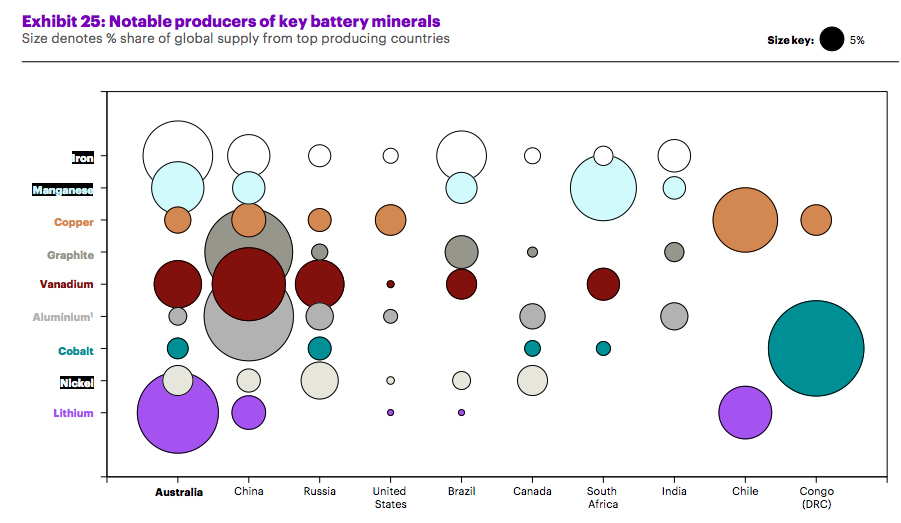

Australia brings to the table critical minerals for battery and renewable equipment, as well as technology, while India could offer solar module and equipment manufacturing, Garg outlines. Both Australia and India are heavily reliant on China for these vital components of the energy transition.

Additionally, Garg says India is already investing heavily in green hydrogen projects locally, and are looking at Australia to set up manufacturing units. India’s government is aiming for the country to produce around five million metric tonnes of green hydrogen annually by 2030 under its National Hydrogen Mission.

One of the key offtakers for the hydrogen is expected to be India’s growing steel industry, which the International Energy Agency (IEA) forecasts could double by 2030 and quadruple by 2050. Australia is the globe’s leading iron ore producer, but does relatively little steel manufacturing – although numerous experts have noted this as the most obvious application for our green hydrogen ambitions.

A recent report from Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF) estimated that for Australia to meet its hydrogen superpower vision, it would need to grow solar and wind capacity to 812 GW by 2050 – a 21 fold increase on today’s levels. Excitement around Australia’s hydrogen potential appears to have weaned somewhat recently, especially following the US’ renewable energy manufacturing policy, the Inflation Reduction Act.

While momentum around hydrogen slows, it has grown around the critical minerals sector, where interest in seeing Australia not just exporting raw critical materials, but also refining and processing them, is growing rapidly. With a number of lithium and rare earth processing projects either recently opened or currently in development, the country is seeking to capture much more of the value chain from critical minerals deposits.

Image: Future Battery Industries Cooperative Research Centre

This slots in nicely with the plans of many of Australia’s political allies, since the globe is currently heavily reliant on China’s processed minerals and materials. For India, which is seeking to massively grow its solar manufacturing sector in the coming years, an alternate materials supply chain is welcome.

A study by the IEEFA and JMK Research found Indian solar module manufacturing capacity could reach 110 GW per annum by 2026. “India will achieve self-sufficiency in solar PV modules at this level and expand exports further,” Garg said.

Australia could also potentially provide India with technologies and expertise in the exploration, mining and processing of critical minerals in light of India’s newly discovered lithium deposits, Garg added.

Australia and India are seeking to establish a comprehensive trade deal, building on the Economic Cooperation and Trade Agreement between the two countries signed last year. Both prime ministers today iterated their hopes such an agreement could be reached by the end of this year.

“The Australia-India relationship is already strong, but we both see potential for growth and an opportunity shape a better future for our region,” Albanese’s media statement read.

“In my first year as Prime Minister, I have met with Prime Minister Modi six times, which underscores the value we place on deepening ties between our nations,” Albanese added.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.