Compressed hydrogen has received little airtime in the future fuel’s global frenzy, especially in Australia. Determined to remain a global energy provider by switching exports from brown to green, Australia is infatuated with the question of how to get its hydrogen to the jaws of a hungry global market.

Viewed from this angle, liquified hydrogen, which involves cooling the loose hydrogen gas until it tenses up and becomes a liquid, looks far more attractive as you can fit five times more of the shrunken molecule in a vessel. Ammonia, which is composed of one nitrogen atom bonded to three hydrogen atoms, is sexier yet – boasting a density of seven times hydrogen gas. “It all comes down to how much you can make and get to your market. That’s what I think is front of mind,” Scott Hamilton, senior advisor and consultant at the Smart Energy Council, told pv magazine Australia.

While attention has fixated on hydrogen’s thicker cousins, West Australian company Global Energy Ventures (GEV) viewed the issue of transport from its own unique lens. Having spent four years designing a ship to transport compressed natural gas, the company’s dozen employees asked figured why not apply same principles for hydrogen.

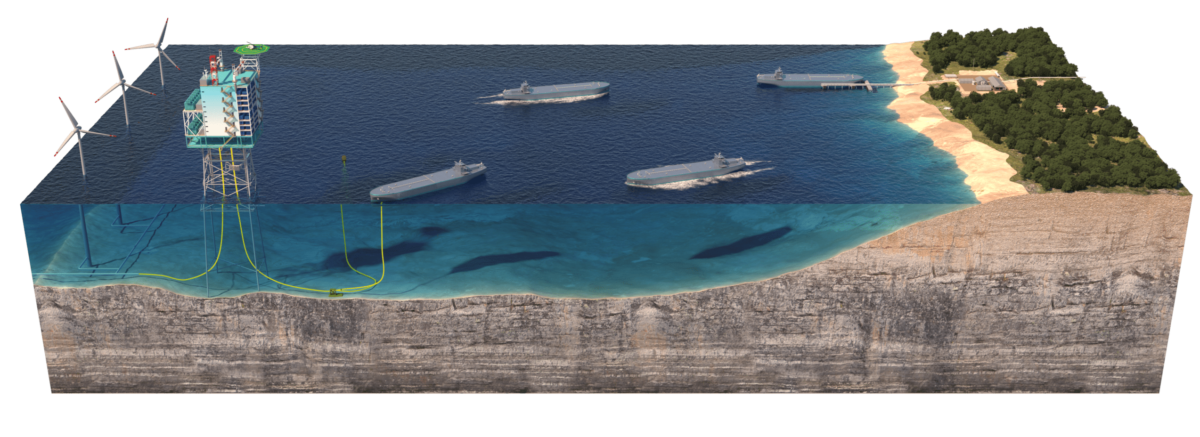

Image: Global Energy Ventures

GEV released its design for a vessel which would not only transport, but also run on, compressed hydrogen in October 2020. It then went a step further, commissioning GHD Advisory to undertake a scoping study weighing up compressed hydrogen against ammonia and liquid hydrogen as an end-to-end zero emissions supply chain. To industry surprise, compressed hydrogen emerged far from the plain Jane it had initially seemed.

“We’re not trying to dismiss the alternatives. Overall, in the next 10 years I think everyone can get there… the point is that the simplicity and efficiency of our [supply chain] should be considered,” Global Energy Venture’s Executive Director, Martin Carolan, told pv magazine Australia.

While the company’s clearest offering is its ship concept, Carolan is urging industry to take broad perspective when it comes to compressed hydrogen. “This is about the end-to-end supply chain, not just the ship.”

Much like the Smart Energy Council, he believes if Australia wants to deliver green hydrogen, it should design its entire supply chain to be emissions free. “Compression lends itself to that quite easily,” he said.

The infrastructural case for compressed hydrogen

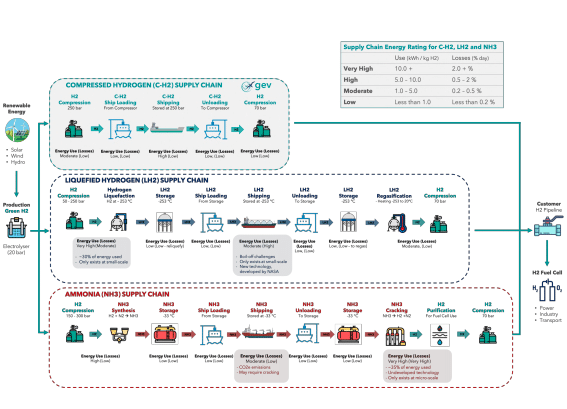

The crux of the case rests on speed and simplicity. Since hydrogen exists as a gas, compression involves fewer energy-intensive conversions and less specialised infrastructure.

Both gas lines and the infrastructure used to load and unload compressed natural gas can be repurposed to carry compressed hydrogen. “That’s why we talk about minimal technical barriers, we just need to [get approvals for] the ship. The other components in our supply chain will be there and ready to go.”

Of course, the repurposing isn’t quite that easy. Traditional gas lines can only carry a blended gas of up to 15% hydrogen. And for SEC’s Scott Hamilton, the rosy picture comes with a caveat.

“There’s quite a lot of debate about whether we should be encouraging the injection of renewable hydrogen into existing gas networks,” he told pv magazine Australia. “When we look at the idea of injecting the gas [hydrogen] into existing pipelines, we need to be very cognisant… to make sure we have excellent leak protection and repair systems and processes in place to make sure that we’re not inadvertently causing a major problem.”

Be that as it may, Hamilton is pro repurposing, at least for the time being. “I’m encouraging doing that as a short term measure. In the longer term, we’re going to need purpose-built infrastructure and pipelines.”

This infrastructure leg-up is vital. Carolan estimates it would be possible to get a compressed hydrogen supply chain up and running in three to five years, if all goes right with its ship design approvals.

On the other hand, some estimates place commercial liquid hydrogen and ammonia supply chains a decade away. As it stands, we simply don’t have the technology needed to make liquid hydrogen commercially viable nor to make the ammonia supply chain zero emissions. “There’s still technical advances needed there,” Carolan said.

Ammonia and liquid hydrogen’s embedded issues

Liquified hydrogen needs to be stored at -253°C to remain liquid – no easy feat, especially on a global voyage. Likewise, because ammonia throws a nitrogen atom in its hydrogen mix, end users wanting pure hydrogen will need to ‘crack’ their ammonia once it arrives, essentially snapping the molecule apart.

It also takes a lot of energy to shrink molecules and crack them apart. If the aim of the game is a completely zero-emissions supply chain, Carolan argues ammonia and liquid hydrogen are both on the back foot.

Scott Hamilton is less worried by these issues. He thinks the technical hurdles to commercialising green hydrogen supply chains can, and will, happen “quicker than expected.”

“Similar to how we’ve underestimated how quickly the cost of solar, wind and now batteries would drop – I think we’ll now see the cost of electrolysis, liquefaction also drop,” he said. “But that doesn’t mean there’s not going to be timing and sequencing issues, and it doesn’t mean there’s not going to be a role for different forms and types of hydrogen.”

Global Energy Ventures

A situation of ‘both, and’ not ‘either, or’

For Hamilton, green hydrogen’s formational journey is less a story of dogged competition than one of multiple pathways.

“We have to let the 1000 green hydrogen roses bloom to see what is going to make the best. I think everyone is going to have a view on this, and I really encourage that. What we’ve really got to do is get these projects happening and get this occurring so we can find out.”

With green hydrogen markets expected to grow tenfold in the coming decades, Hamilton believes there will likely be room for the market to accomodate hydrogen’s multiple forms.

“I think there’s going to be various markets and demands for renewable hydrogen in different forms,” he said. “It’s likely to be an ‘and’ not an ‘or.’”

Potential in off-shore wind platforms

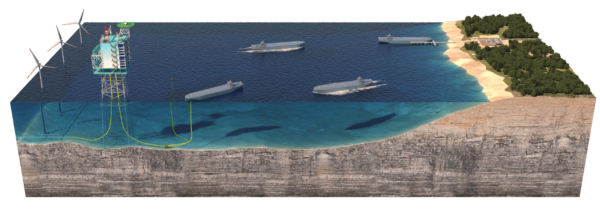

Carolan says he’s been in discussions with a number of European companies which are exploring the possibility of producing green hydrogen on offshore wind platforms when extra capacity is available. While not far from shore, the green hydrogen will still need to find its way to land.

“There will be instances where a pipeline will work, and instances where a pipeline will not work. So what’s the alternative? We think that compression is ideally suited to that part of the world, with much shorter distances.”

Global Energy Ventures

Carolan proposes it would be quicker and easier for these companies to compress their hydrogen and let GEV’s ships ferry it the half day to shore, rather than turning it into a liquid or ammonia only to convert it back into gas a few hours later.

“It just doesn’t make sense to us that you would run through such extensive chemical capital and energy-inefficient processes just to move the energy source… from A to B.”

Sights set on southeast Asian markets

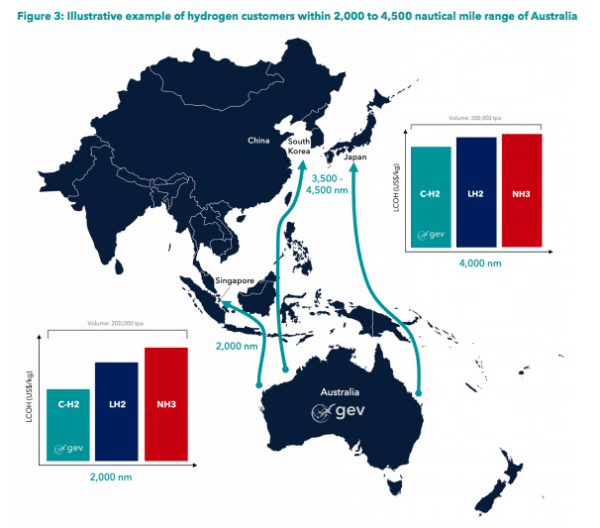

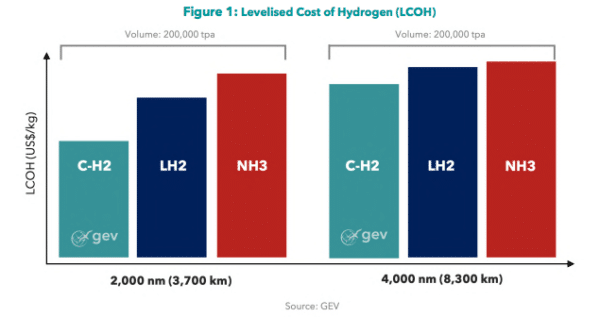

Yet compressed hydrogen isn’t only fit only for short distances, the company insists. Its scoping study found compressed hydrogen is “extremely competitive” compared to ammonia and liquid hydrogen when shipped less than 2,000 nautical miles. It remains competitive up to 4,500 nautical miles – roughly the distance between the north half of Australia to southeast Asia.

“That was a revelation for the industry because no one had ever thought that compression, from a shipping perspective, would be in the mix for that distance,” Carolan said.

Global Energy Ventures

Buoyed by the results of the study, Carolan says GEV’s green hydrogen supply chain is destined for countries like Japan, South Korea and Singapore. “It’s really not clear how big the market is, but we know that within a regional context, if it’s today a 10 million tonne market then it’s going to grow tenfold.”

He’s confident the simplicity and efficiency of GEV’s supply chain will mean its able to provide green hydrogen to southeast Asia before the liquid hydrogen and ammonia supply chains are established. “We’re a three to five year scenario for having our ship ready.”

Forget exports, decarbonising shipping alone is a windfall

While the Smart Energy Council are as excited as anyone about the potential for Australia’s green hydrogen export market, Hamilton noted decarbonising global shipping alone would be a jackpot for well-positioned companies.

“That’s a huge opportunity for Australia and for companies like [Global Energy Ventures] to be involved in.” As he pointed out, experts expect $1.9 trillion worth of investment will be needed to decarbonise shipping by 2050.

“I’m happy to be collaborating with these guys [GEV], I think they’re really doing some very exciting work in terms of the development of these new technologies,” Hamilton added.

In search of partnerships

This type of collaboration – or more specifically, partnership – is precisely what GEV needs to proceed to the next stages of its proposal.

After it revealed the design for its compressed hydrogen vessel less than six months ago, GEV was approached by fuel-cell manufacturer Ballard Power Systems. “It really solidified for us that we were on the right track,” Carolan said. The two companies are now formally working together to get the ship’s propulsion to be as efficient as possible.

GEV is yet to sign any agreements with partners in the two other areas it seeks them though – namely in the form of Australian green hydrogen production projects and end users.

It is hoping to strike a deal sometime this year with a hydrogen production project located anywhere between the mid-west of West Australia, across the Northern Territory and down to Queensland’s Gladstone.

The ultimate goal is to partner with a project which could create at least 30,000 tonnes of green hydrogen annually. Such a scale would warrant the construction of three demonstration ships which GEV would use to prove, and hopefully commercialise, its compressed hydrogen supply chain.

Global Energy Ventures

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

2 comments

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.