Australia’s reliance on imported transport fuels like petrol and diesel has grown in the last three years, even as the pandemic laid bare the problem of global supply chains more recently enflamed by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Today 91% of the fuel Australia uses for transport is imported. “We do not have fuel security,” Zali Steggall, the Independent Member of Parliament for Warringah said yesterday at the emergency summit held by the Smart Energy Council in Sydney, pointing out national fuel reserves are pitiful.

There was uniform consensus about Australia’s vulnerability among attendees, which also included Admiral Chris Barrie, former Chief of the Australian Defence Force; Cheryl Durrant, Climate Energy Strategist and executive member of the Australian Security Leaders Climate Group; Behyad Jefari, CEO of the Electric Vehicle Council; Richie Merzian, Director of the Energy and Climate program at thinktank the Australia Institute; as well as many more specialists. Given this, the event concluded by drawing up a shortlist of enactable solutions. Below is what the assembly arrived at.

Bella Peacock/pv magazine

1. Introduce international vehicle emissions standards

Essentially a standard imposed on car manufacturers, Australia has resisted bringing in vehicle fuel efficiency standards which have long been commonplace among our peers. In fact, in the developed world only Australia and Russia remain without the standards that cover 80% of the world.

The standards would put a monetary impetus on vehicle manufacturers to ensure the cars they import emit less pollution and have better fuel technology and efficiencies, EV Council CEO Behyad Jefari said.

The lack of these standards, he added, has made Australia “a dumping ground for less efficient vehicles,” giving carmakers a market for the models deemed unfit overseas.

Vehicle emissions standards were posited as one of the top solutions because, importantly, they would not cost the government nor citizens money to introduce and there is already a well established international framework in place which could be enacted immediately.

Be that as it may, Steggall told the event that when she raised the issue with the Federal Energy and Emissions Reduction Minister Angus Taylor, “I got an answer that this would not be addressed until 2027.”

Independent candidate for North Sydney Kylea Tink committed to introducing a private members bill for vehicle emissions standards in Australia, should she be elected next month.

Tink said the Morrison government had been looking into vehicle standards back in 2016, but had for reasons unknown opted not to implement them.

Jefari estimated the introduction of such standards would save Australian motorists between $500 – $660 annually, and would save the economy $30 billion currently flowing overseas to pay for fuel. The standards would also help to reduce annual emissions by 22 million tonnes, he added.

2. Mandate the electrification of government fleets at local, state and federal levels

Electric vehicles (EV) are the most obvious way to shift Australia’s fuel reliance as they make petrol and diesel redundant. There are, however, numerous issues impacting their uptake, which we will discuss shortly.

Image: ARENA

In the meantime, it’s noteworthy that over 70% of cars purchased in Australia are from the used car market. Given that, government fleets take on a new importance as a tool for bringing electric vehicles into that second hand market.

If all levels of government, from local, state and federal were mandated to purchase electric vehicles in future, it would not only stimulate the construction of more public charging points by growing EV penetration, but would eventually give middle income Australians access to the technology.

3. Set emissions and EV targets

Considered another “easy win” because of its no cost nature, setting and legislating proper short-and medium-term targets for emissions and EV sales would force governments to build policies to stimulate the decarbonisation of transport.

Importantly, as Jefari pointed out, there is already a huge appetite for EVs in Australia – but many people simply can’t get their hands on them.

He claimed that for every EV model imported into Australia, demand is between 10 to 20 times greater, with batches selling out within hours of being made available online. Waitlists for some models are as great as 15,000 for cars bring brought in 500 at a time, he added.

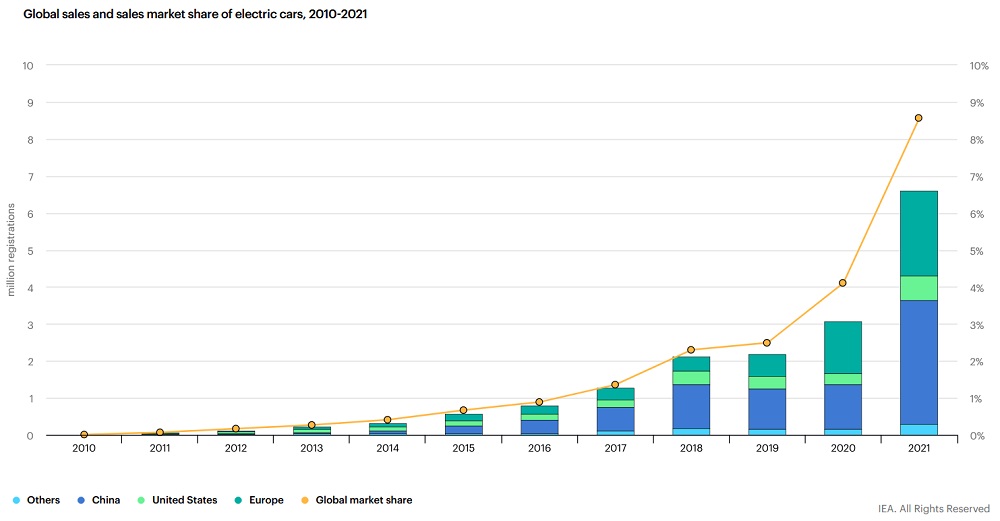

International Energy Agency (IEA)

So the problem is not that Australian don’t want EVs, it’s that the current landscape in Australia hasn’t made them accessible.

The thinking is that by setting targets, it would force policymakers to rectify this. While this shouldn’t technically be difficult (given most developed countries have trodden the path before us), it is a duty for which there seems little political will federally.

4. Invest in public transport, bike and footpaths

Helping Australians become less dependant on private vehicles is perhaps one of the most impactful sustainability pathways. Giving Australians, who have historically been extremely reliant on personal vehicles, access to better public transport and better bicycle and footpaths is a fairly obviously means to cut emissions from transport – though this is more suitable for urban cities than regional communities.

As Admiral Chris Barrie pointed out, Australia’s per capita energy consumption in 2022 is forecast to be 10,071 kWh. For our neighbour Indonesia that number sits at just 812kWh.

Behaviour and how Australians consume energy, the admiral noted, must be addressed.

5. Remove GST [goods and services tax] from EVs

Pretty self explanatory, removing additional taxes would accelerate the adoption of electric vehicles by making them cheaper.

6. Get rid of diesel rebates and fossil fuel subsidies

Again, self explanatory but a key component here, it was noted, is messaging.

EVs need to be sold as “fuelled on Australian sunshine,” John Grimes, CEO of the Smart Energy Council said. With Australia’s world leading solar penetration, it is entirely feasible that instead of running on imported fuel, our vehicles could be powered by the wind and solar generated here onshore.

This hook could be a key selling point for the technology, making the subsidisation of fossil fuels even less sensical.

ANU Solar Racing

7. Introduce a Storage Energy Target

Think Renewable Energy Target (RET), but for storage. Introduced by the Howard government back in 2001, Australia’s RET has been hailed as a driving force behind the country’s staggering solar uptake.

Since the core element of EVs is their battery, introducing a storage target would also stimulate the EV market. Moreover, given that EV batteries have larger capacities than most household batteries and their vehicle-to-grid (V2G) capabilities are increasingly being recognised, such a policy could have multiple benefits. For instance, it could help smooth our grids, which are rapidly becoming overloaded with solar power during daylight hours.

Image: Tesla

Moreover, Allegra Spender, CEO of the Australian Business and Community Network and independent candidate for the Sydney electorate of Wentworth, says such targets – not only for storage, but decarbonisation generally – would help the business and corporate world understand Australia’s direction and move toward it. The current disparity between ambitious state goals and federal inaction has created uncertainty and ultimately slowed corporate initiatives, it was said.

8. Repurpose oil refineries for future fuel industries

Five Australian refineries have closed in the last decade leaving only two Australian refineries in operation today, Australia Institute’s Richie Merzian said. This is a major reason why Australia’s reliance on fuel imports has grown in recent years, the Australia Institute report ‘Over a Barrel’ released on Thursday noted.

The repurposing of these sites is something pv magazine Australia reported on last year when global infrastructure developer AECOM examined all 58 petroleum fuel refineries and storage & import terminals in Australia and New Zealand to assess their capacity to be repurposed for new renewable industries.

It found many had significant potential, including seven ‘unicorn sites’ which AECOM described as uniquely flexible and therefore especially valuable.

Image: Exxonmobil

These sites would be ideal locations to develop hydrogen industries and renewable future fuels, according to both AECOM and event attendees.

9. Reskill & redeploy workers to build onshore manufacturing capacity

As mining shifts away from fossil fuels and towards critical minerals needed for batteries, workforces will need to be retrained and redeployed. Australia is already one of the world’s leading exporters of battery raw materials but the country does very little onshore processing and refining, and virtually no manufacturing.

This is something government and industry is trying to kickstart, and the coordinated reskilling and ultimate redeployment of workforces will prove critical to this vision being realised.

Image: Wollongong City Council

It isn’t only batteries which hold new industry potential, but also hydrogen. Given many of the country’s hydrogen hubs are being proposed in coal regions, an obvious choice due to their preexisting infrastructure, a more concerted start to the reskilling process would aid this transition and build future industry, attendees suggested.

10. “Vote like your life depends on it – because it does”

This pertinent line was thrown out in the event’s closing discussion, and was a sentiment shared by many in the room.

The 77-year-old Admiral Chris Barrie called next month’s election the “most important” in his lifetime. He criticised the Coalition’s near decade in power as being characterised by “squandered opportunities” in terms of climate action and resilience.

It was agreed that Australia won’t be able to plug its massive fuel vulnerability without building scaffolding on which decarbonisation can hang.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

Makes a lot o sense

I would have thought fuel security should target food security 1st. I can always cycle to the supermarket but in order for there to be something on the shelves I need (green) hydrogen servos on freight routes and solar/wind fed electrolysers on farms producing fuel and fertiliser.

Eliminating fossil fuel dependency from our food supply needs prioritising.